A Short History of Ticketing Proxies

For most of history, ticket proxy would have been a guy you asked to wait outside the cinema/theater/stadium to get tickets for the hottest events on the day they started selling. Today, he has been replaced by a computer. But how did this state of business come to be?

The Rise of Online Ticketing

While the exact origins of paperless tickets are debated, Ticketmaster is definitely one of the most influential companies in the field. Even before the ‘90s, it was working on primitive versions of online tickets. Namely, the company put machines in physical stores where people could buy and print tickets instead of going to the location itself. This made use of the growing network infrastructure while also working around the issue of customers not having access to computers, the internet, or printers at home.

But by the mid ‘90s, home computing was growing large enough and the internet accessible enough to facilitate buying tickets entirely online. Ticketmaster launched ticketmaster.com in 1995, while tickets.com was founded around the same time. The people of 1996 didn’t yet have cellphones, let alone smartphones, but the basis was there.

By the time the millennium rolled around and the world failed to end, the adoption of online ticket sales was spreading rapidly, as this enthusiastic 2001 PR piece on theater ticket sales in the UK attests. Meanwhile, Ticketmaster was buying competitors left and right, diversifying its offerings. For example, the TicketWeb acquisition was meant to expand its reach to New York clubs and the San Diego Zoo.

So, there was obviously money in selling tickets. But it’s equally true that there was always money in reselling tickets, especially at a markup, especially for hotly desired events…

The Rise of Online Ticket Scalping

With online ticket sales taking off, secondary businesses started springing up to feed on that. If you had tickets you wanted to sell, you needed a platform for that, and StubHub – launched in 2000 – was built on that premise. Of course, not everyone wanted to use an official platform, and thus ticket resellers found business on Craigslist and Facebook (once those became a thing, anyway). When eBay purchased StubHub, Ticketmaster countered by buying the competing TicketsNow to claim a piece of the ticket resale pie.

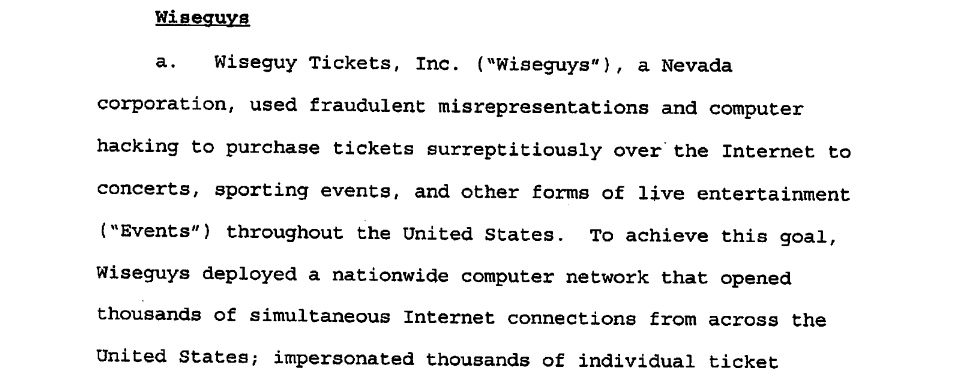

At the same time, online ticket scalping was not far behind official online ticket sales. One of the earliest “successes” was Wiseguy Tickets (also working as Seats of San Francisco) which manipulated fan club memberships to buy up tickets for U2’s Vertigo tour in 2005, earning $2.5 million of profit in the process. When the law finally came down on them in probably the most famous case targeting ticket scalpers, the prosecution alleged that Wiseguys made $25 million during their 2002-2009 streak.

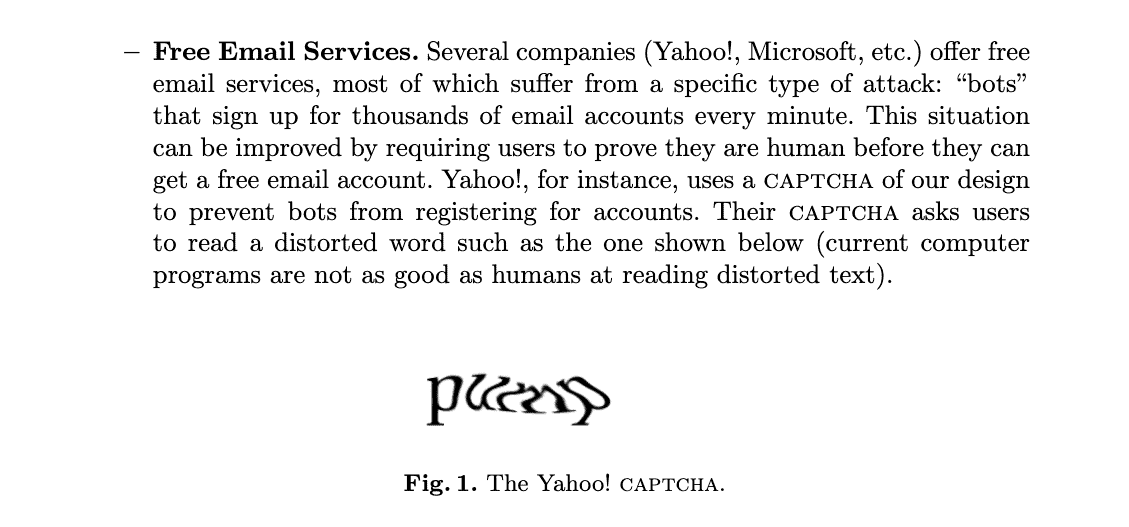

The group used a variety of methods to overcome security measures put in place by ticket vendors – including beating multiple generations of CAPTCHA – all in order to help their employees and bots secure the most lucrative tickets.

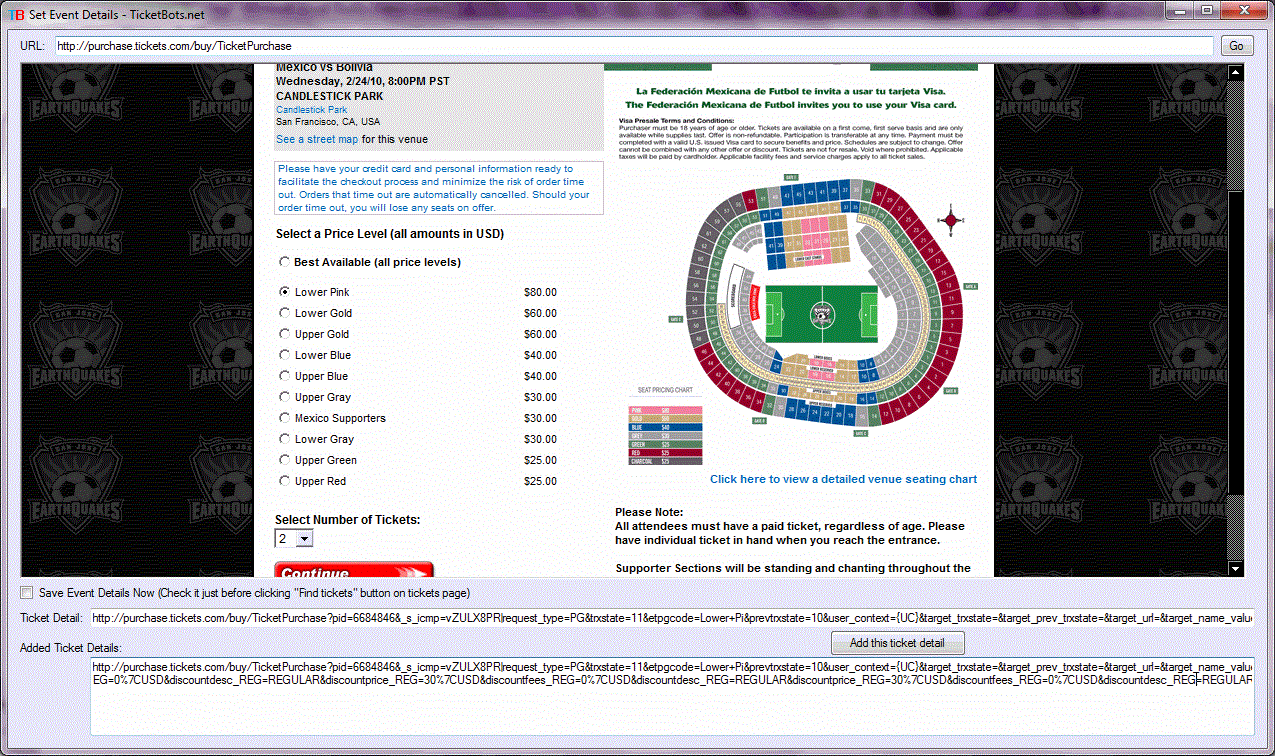

Bots were one of the key components of their illicit success. These automated systems could spot sales and reserve tickets faster than any human could, and could be scaled without compromising the security or the bottom line. After all, bots don’t talk or earn wages. But the bot tactics and innovations are well-documented elsewhere – what’s most important for us is what they did with proxies.

Wiseguys Use Of Ticketing Proxies

Your ticketing bot may be smart, but it can’t do anything if Ticketmaster has banned its IP. To get around the issue, Wiseguys created their own network of proxies.

According to the indictment, Wiseguys started building out covert IP infrastructure around 2007, using shell companies Smaug and Platinum Technologies. Wiseguys registered 100,000 IPs to impersonate legitimate customers. Furthermore, they aimed to rent non-consecutive IPs to hide the synthetic nature of their network.

Wiseguys rented out these IPs from companies providing colocation services by claiming the addresses were for testing internet protocol services or brokering hotel room bookings. As such, they effectively built an infrastructure of what we call datacenter proxies.

The first line of proxies was meant for Watchers, bots programmed to monitor ticket vendors for new events. To operate the Watchers, Wiseguys leased Amazon servers. The moment a new sale was spotted, the server lease was terminated. This hid the connection between Watchers (that were constantly refreshing the website to spot ticket sales) and the actual ticketing bots that would attack in the next wave.

Granted, that whole infrastructure didn’t spring up at once, and neither did the technical adaptations. Moreover, 100,000 IPs wasn’t the end goal, as email correspondence showed Wiseguys’ intent to acquire up to 500,000 addresses.

Others would have reasons to follow in their footsteps. While it’s hard to evaluate the size of the scalping market, some estimates put the ticket resale market in the US in the early 2010s to be worth around $4 billion.

The Technical Adaptations of Ticketing Proxies

It’s difficult to pinpoint when the proxy seller industry as we know it emerged – only that it definitely started with datacenter proxies. Providers merge and rebrand, so research involves turning to internet archives and hunting for snapshots of websites.

Wiseguys made do without any proxy provider – for them, it all started with sourcing datacenter proxies from colocation services. But those IPs are fairly simple to detect: either by getting data from IP geolocation services or just seeing many similar IPs connect at once. They’re also then easy to block, as the ticket seller doesn’t risk blocking actual customers. After all, people don’t live in datacenters and, as such, don’t get datacenter IPs. This made it clear scalpers needed something harder to detect – which led to the rise of residential proxies.

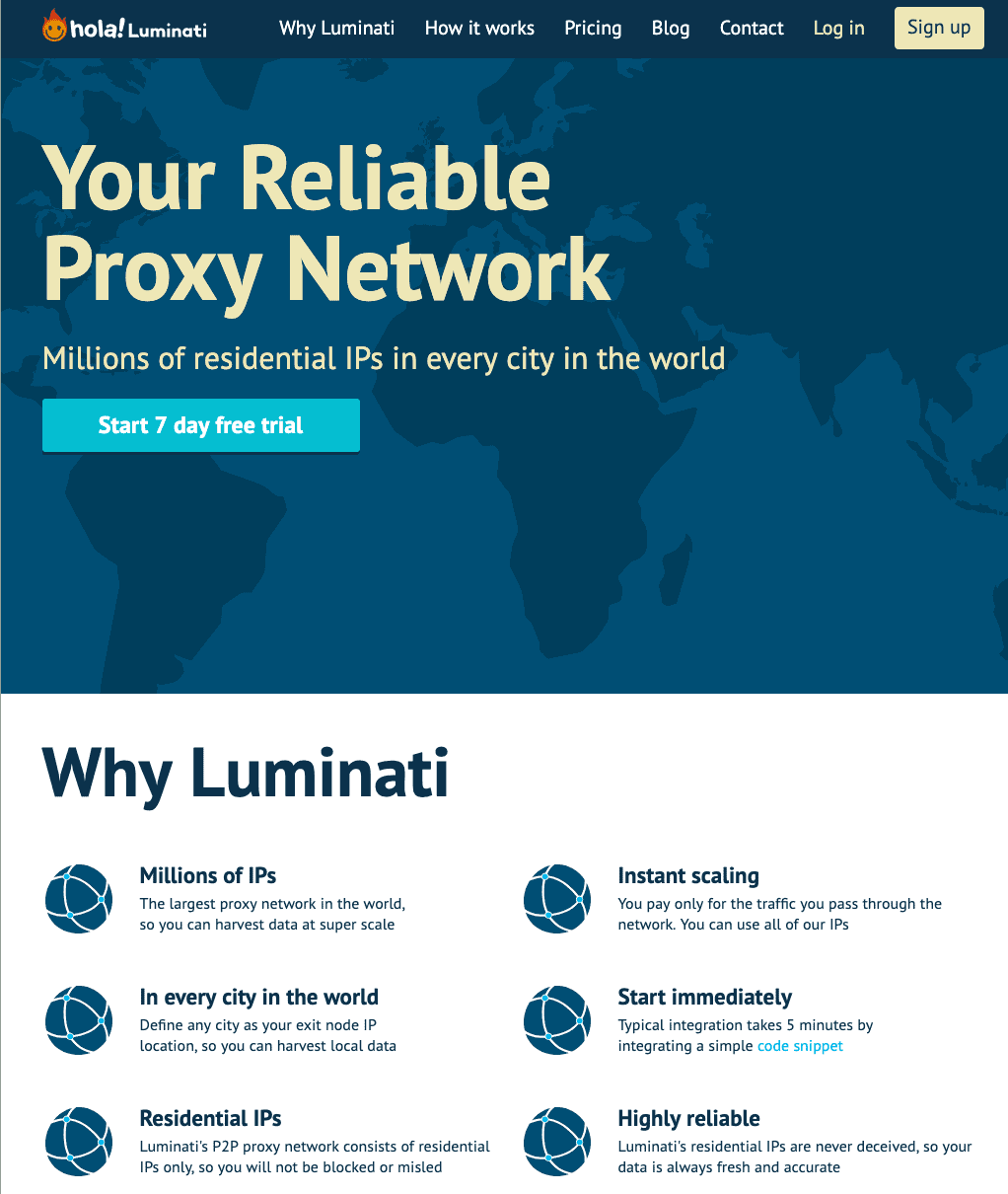

Residential proxies were the natural next step: hosted by real users, their IPs were identified as coming from residential areas. They would be harder to block, too – you may be blocking a paying customer!

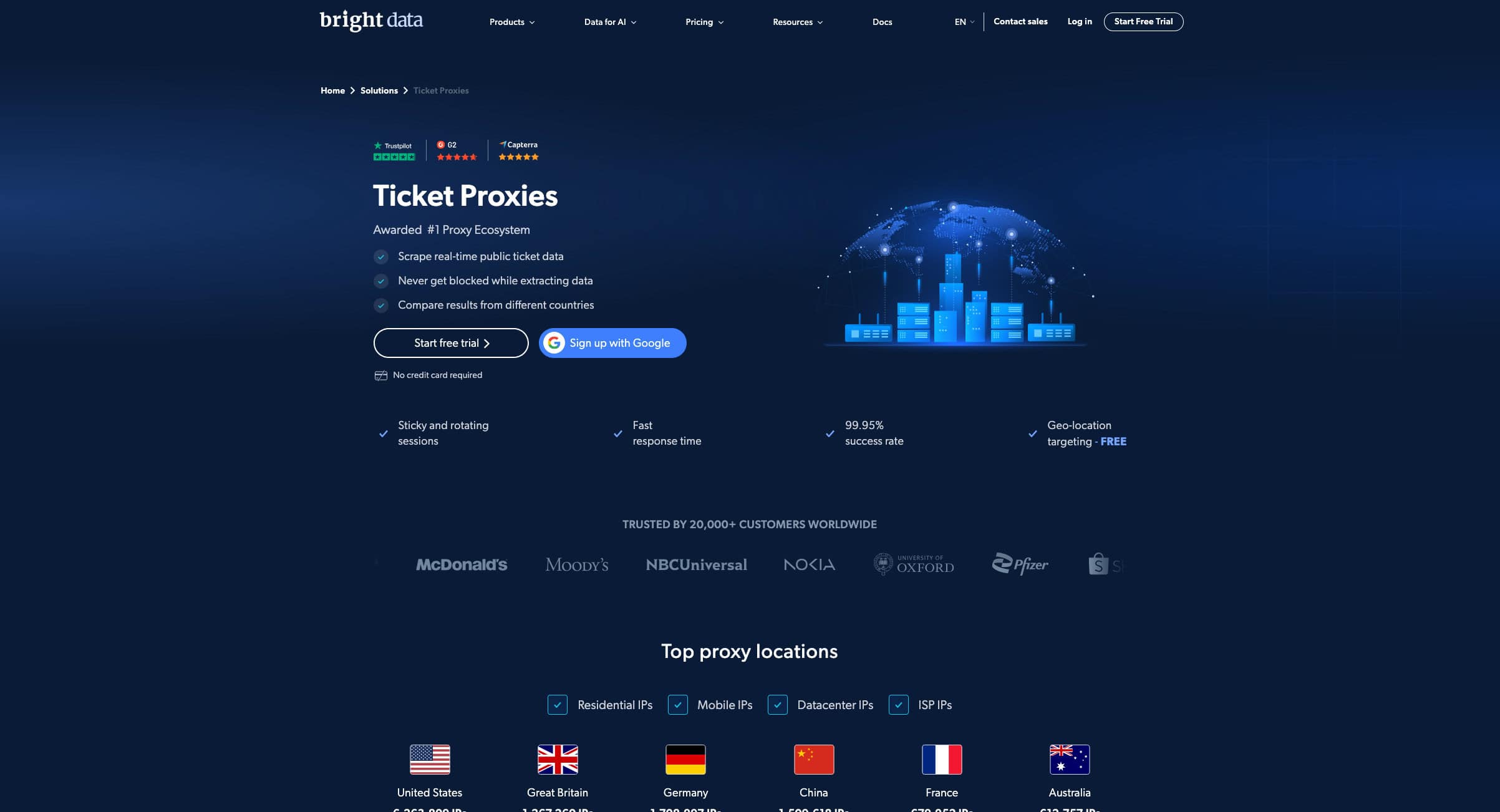

According to the scarce historical data, Luminati – that’s Bright Data before the rebrand – was marketing itself as a peer-to-peer VPN provider up till the end of 2015. From 2016, it started positioning as a proxy network with residential IPs. And if we go over Oxylabs’ archives, residential proxies as a specific product appeared in May 2018.

There was also (and probably still is) a shadier undercurrent of residential proxy vendors. 911 S5 was a massive supplier of proxies that started operations in 2014 before it got shut down by the FBI in 2020. It used six free VPNs to turn 19 million devices into residential proxies and reap around $100 million in profits. The existence of malicious actors like these certainly siphoned off some of the demand.

It’s unclear when the untraceability of residential proxies became a large enough selling point for them to be legally marketed as a specialized product for ticket scalping. But we do know that the sneaker scalping craze was taking off in 2018, spurring a niche market that was looking for alternatives to datacenter proxies.

While sneakers weren’t directly tied to ticketing, the two markets developed in parallel and pushed proxy suppliers to adapt. For a long time, both sneaker releases and ticket sales worked on the first-come-first-serve-principle. As such, scalpers needed more speed, and bots could only work as fast as the internet connections allowed. This is where proxy suppliers had to adapt – speed was essential, and ISP proxies offered it.

ISP proxies combined the speed and reliability of the datacenter proxies with the untraceability of the residential ones. But this solution didn’t work forever. Eventually, sneaker sales moved to a raffle system (as for tickets, various artists had tried doing that even in the Wiseguys days) and speed lost prominence as a selling point. Still, ISP proxies remain a staple of proxy suppliers to this day.

For all the evolutions of the proxies, bots are still the most important part of the technological arms race. CAPTCHAs never stopped changing; security measures to detect bot-like behavior demanded new types of bots that would act sufficiently human-like, and so on. There are far more vectors for bot detection and obfuscation than there are for proxies.

But the fight doesn’t end there: tackling scalpers solely via technological effort would mean playing catch up with a decentralized group of heavily financially-incentivized and inventive people. That’s why ticket scalping has long been combated on another front: the law.

The Legal Backlash to Ticketing

Web data scraping had been around for almost as long as the internet was, but it was rapidly increasing in prominence around the same time as sneaker copping. This was great news for proxy providers, as they could increasingly diversify their markets. Meanwhile, the legislators were somewhat catching up with the idea that automated ticket scalping is potentially harmful to consumers.

For example, in 2016, the US passed the Better Online Ticket Sales (BOTS) Act. In the Federal Trade Commission’s own words, “the law outlaws the use of computer software like bots that game the ticket system.” More than that, it also outlawed the sale of tickets that were knowingly obtained via such methods.

Other countries have also been working on similar legislation. The UK passed a law in 2018 that would put potentially unlimited fines on “ticket touts” (that’s how the scalpers are called in the UK) for using bots. The Canadian province of Ontario implemented a similar rule in 2017. In Taiwan, both scalping and using proxies to get tickets are against the law.

The effectiveness of the BOTS Act was, however, dubious. There was one case in 2021 when three ticket brokers were sentenced to pay $3.7 million in damages (as they were determined to be unable to pay the full $31 million sum set earlier). It was the most serious case brought before the public. This in part prompted President Trump to issue an executive order on March 31st, 2025 to make the FTC more rigorously enforce the BOTS Act.

The enforcement of such laws remains fairly weak outside the US as well, especially when the act of scalping itself often remains unregulated and thus very lucrative. For example, the parts of the Ontario law targeting specifically scalping were rolled back in 2019 after a change of government. Taiwanese officials are currently considering making ticket purchases tied to your real name as a way to impede scalpers.

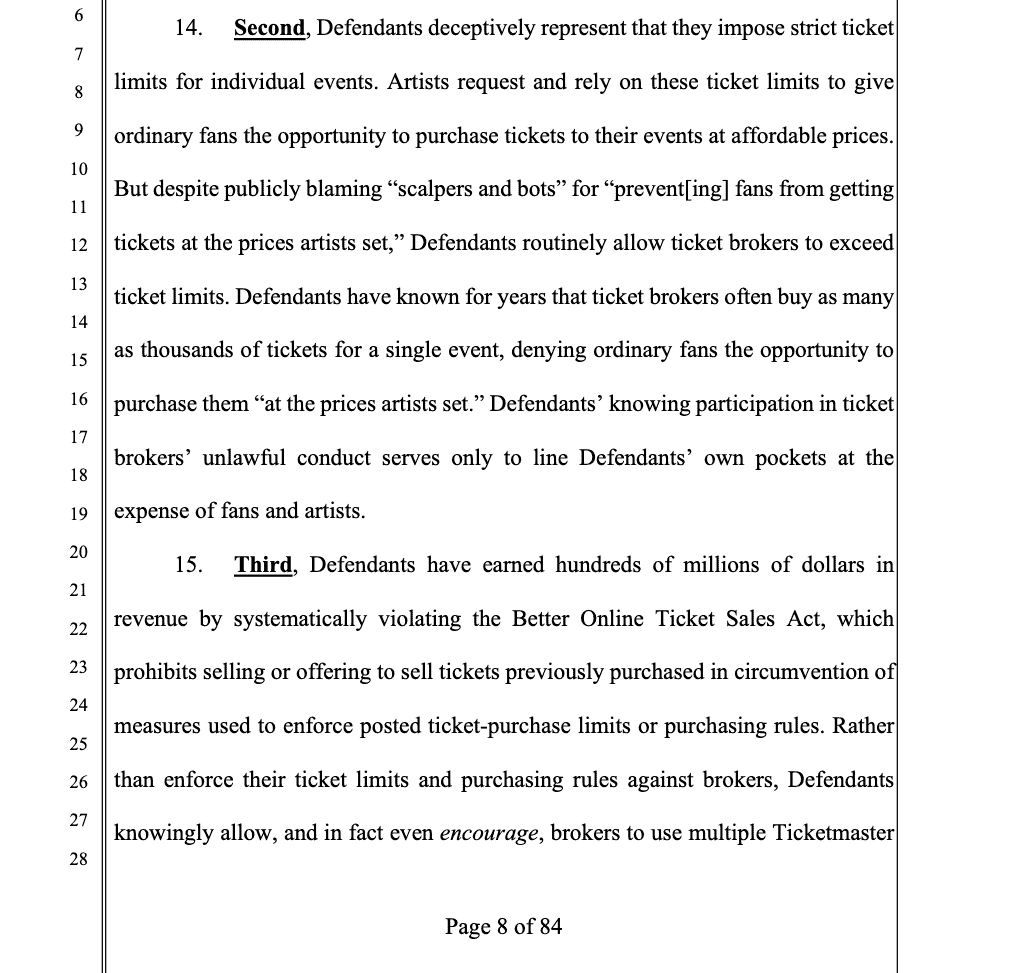

The serious implementation of such laws is also impeded by scalpers’ (alleged) secret ally: ticketing agencies themselves. You may remember that Ticketmaster had purchased a ticket reselling company to get a cut of both sales and resales. However, recent Ticketmaster and Live Nation lawsuits by the US Department of Justice and then the FTC claim that the companies knowingly allow scalpers to purchase tickets beyond their set limits (via multiple accounts) – among other shady practices.

Between weak and uneven enforcement of anti-scalping and ticketing laws and actors in the anti-scalper space, this leaves space for scalpers to survive and thrive. The profits of servicing this market don’t seem to be large enough for large companies to risk it, but the risk-reward calculation seems good enough for smaller businesses. This is also reflected in how the marketing treats this use case in the current day.

The Life of Modern Ticket Proxies

Today, there aren’t proxy providers that would market themselves as selling exclusively ticketing proxies – at least not publicly. Besides, this would be somewhat limiting when you consider the many use cases proxies have today. However, the providers’ overall attitudes towards this specific niche are varied.

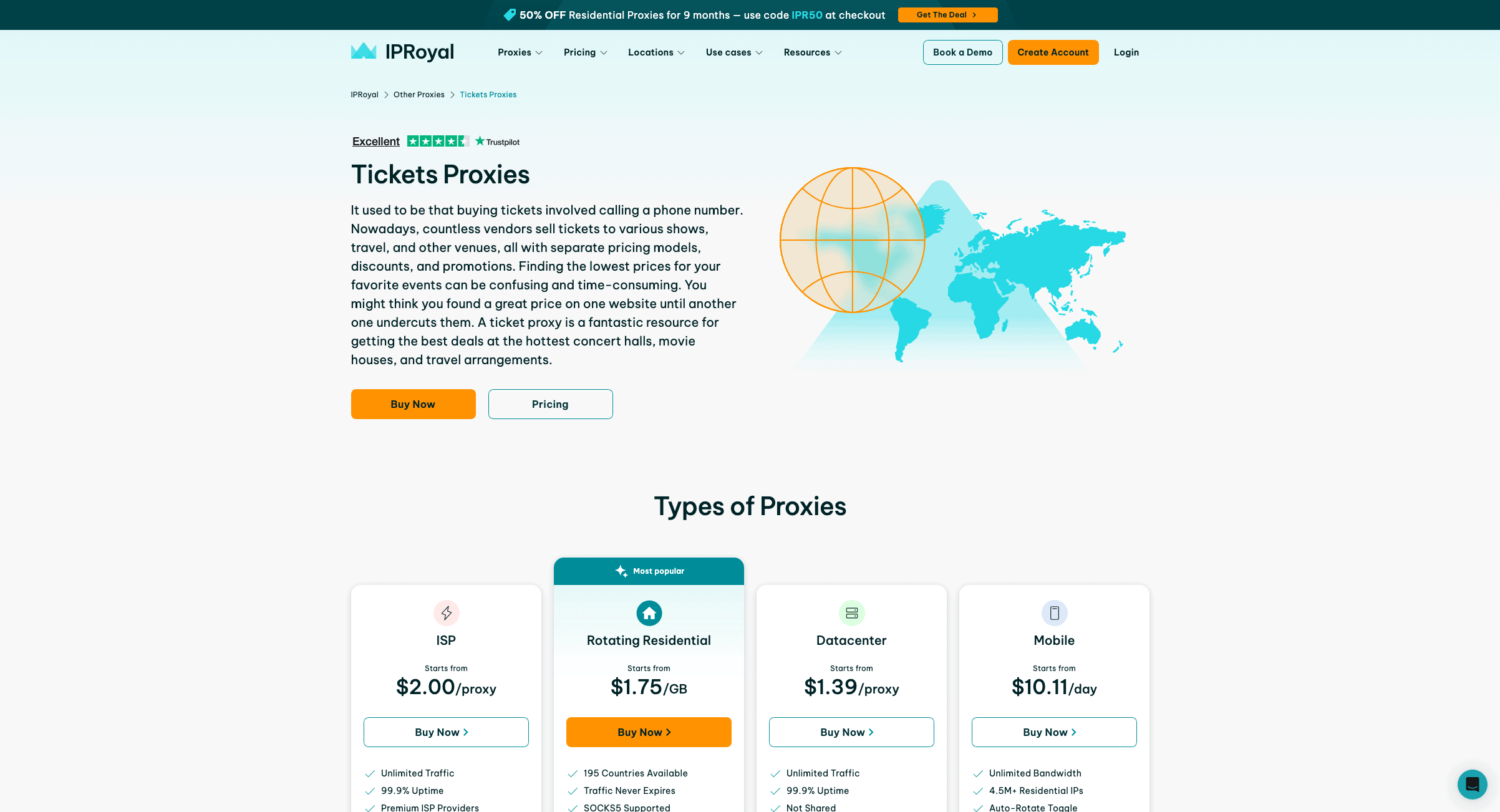

As of September 2025, some prominent proxy providers either directly marketed proxies for ticketing or at least endorsed the use of their product for reselling:

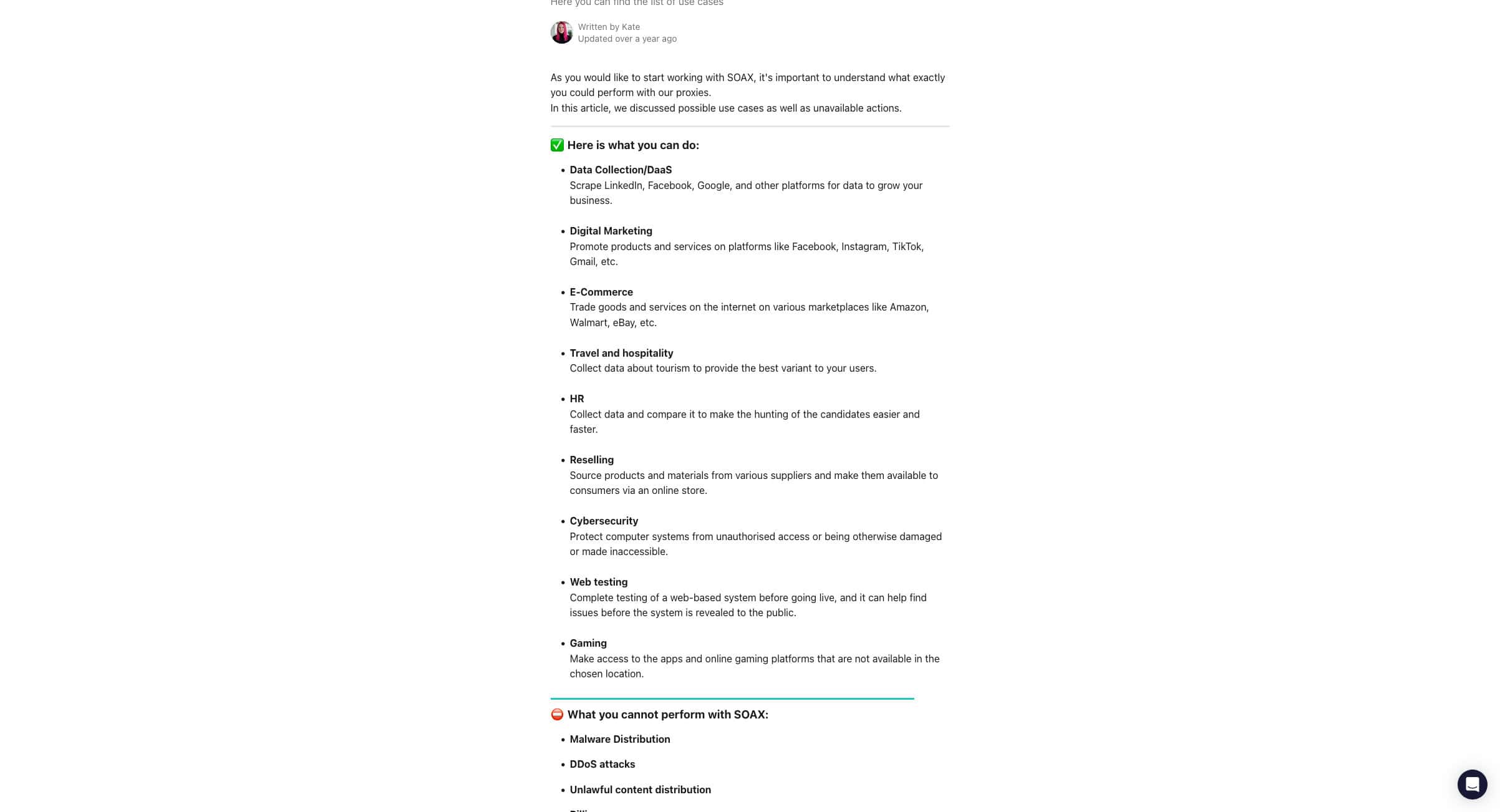

Other major proxy providers forbid the use of their products for ticket scalping purposes:

But while reputable large enterprises might not be too hot on ticketing, smaller providers are seizing on the opportunity:

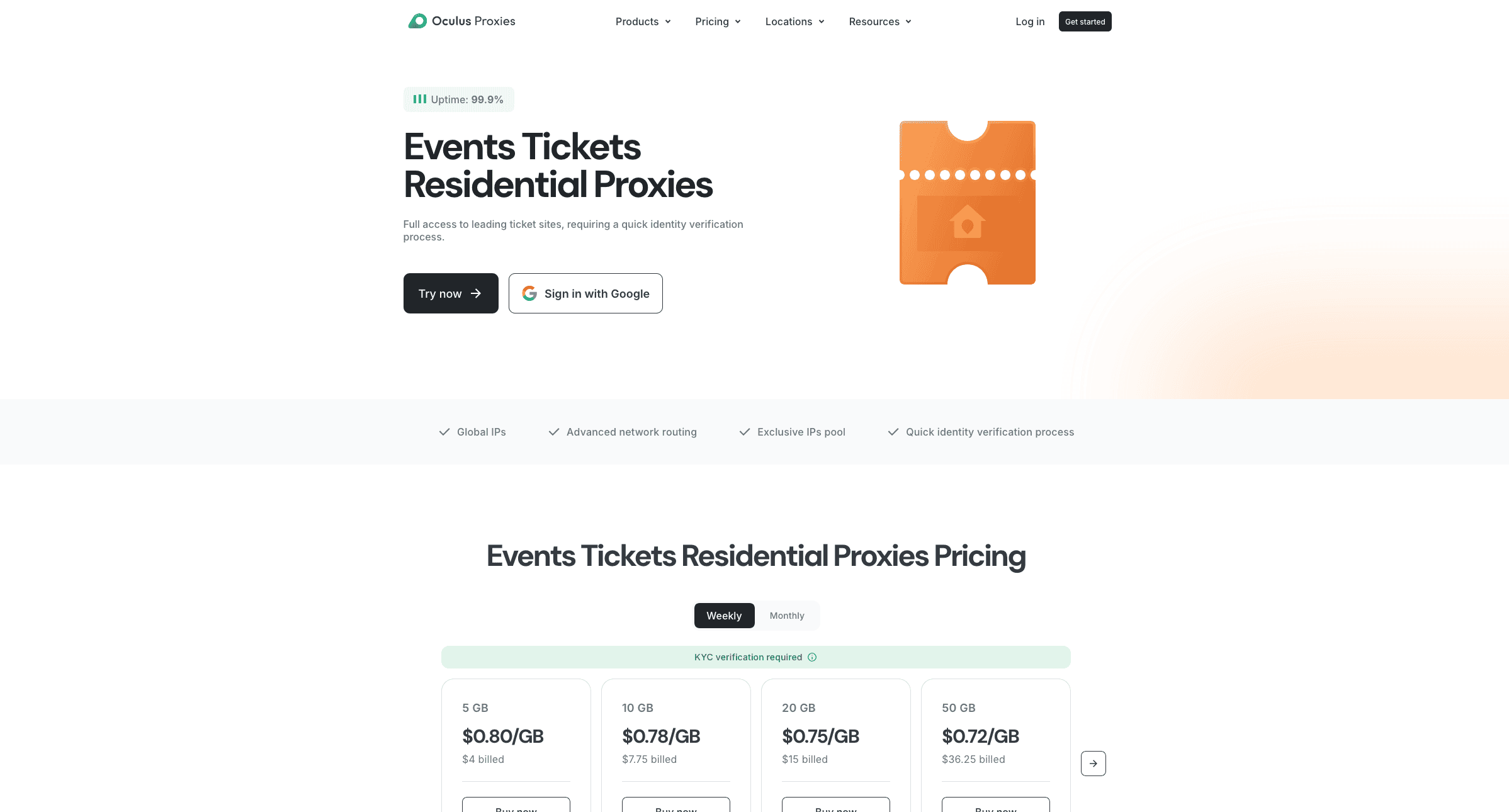

ISP proxies are now marketed for the ticketing crowd by smaller and more specialized proxy providers:

In Conclusion

Proxies have been an inextricable part of digital ticketing for almost as long as it existed. However, while they’re vital in enabling the process, they’re not nearly as crucial as ticketing bots. We can already see major proxy providers ditching or outright banning ticketing as a use case for their products.

As web scraping becomes an increasingly important feature of e-commerce, proxies have other reasons to proliferate and develop. And all those developments are likely to be, one way or another, useful for ticketing. Therefore, the history of ticketing proxies is the history of commercial proxies in general. And that is a lot less criminally tantalizing!