Web Scraping API Report 2025

Welcome to our annual report on web scraping infrastructure. This edition includes two parts. The first is technical: it benchmarks nearly a dozen popular web scraping APIs, aiming to determine their effectiveness and cost of unblocking protected websites. The second part is exploratory: there, we try to analyze how the AI boom has affected our industry.

All in all, it’s been a transformative (you could even say: hectic) year that’s introduced many new players, made the incumbents reconsider their position, and placed web data access at the center of a trillion dollar gold rush.

Summary

- Our unblocking test included 11 scraping APIs and 15 protected websites.

- Four providers (Zyte, Decodo, Oxylabs, and ScrapingBee) managed to open them over 80% of the time, with Zyte leading the way.

- Zyte’s API was also among the fastest to return results; ScraperAPI, Decodo, and Oxylabs followed.

- Shein, G2, and Hyatt gave our participants the most trouble, with nearly a half failing to scrape them.

- Providers with variable pricing models (Zyte, Zenrows, ScrapingBee & ScraperAPI) had the cheapest base rates, but their top configurations charged up to 100x more!

- With our methodology, which involved JavaScript & premium unblocking mechanisms, Decodo cost the least.

- By August, AI companies had received nearly as much funding in 2025 as non-AI startups. This has created a new generation of US-based web scraping infrastructure providers like Firecrawl and Browserbase.

- Their novel approach to AI-based parsing, cloud browser management, open source tooling, and crawling strategies has forced entrenched companies to play catch-up.

- Despite the narrative shifting to AI agents, LLM training continues to generate the bulk of web traffic, now focusing on multimodal data.

- Growing attention to web scraping is bringing negative consequences, with Cloudflare and Google intensifying their determent efforts and the anti-bot industry experiencing fast growth.

State of Unblocking

Participants

Our research includes 11 major providers of web scraping APIs. Most gave us access after approaching them directly. We bought Firecrawl and ZenRows on our own.

| Participant | Target audience |

|---|---|

| Apify | Small to medium customers |

| Crawlbase | Medium to large customers |

| Decodo | Small to medium customers |

| Firecrawl | Small to medium customers |

| NetNut | Enterprise |

| Nimble | Enterprise |

| Oxylabs | Enterprise |

| ScraperAPI | Small to large customers |

| ScrapingBee | Small to medium customers |

| ZenRows | Small to medium customers |

| Zyte | Medium to large customers |

Methodology

We informed the participants about our general methodology but didn’t disclose the list of websites in advance. The intent was to avoid preemptive optimization.

We ran the bulk of our tests in October 2025.

We chose 15 targets for our benchmark. The selection criteria for these websites were 1) popularity and 2) being protected by major anti-bot vendors.

| Target | Property | Bot protection |

|---|---|---|

| Allegro | Product | DataDome |

| Amazon | Product | In-house |

| ChatGPT | Logged out answer | Cloudflare / login wall |

| G2 | Company reviews | DataDome |

| SERP | In-house | |

| Hyatt | Search result | Kasada |

| Immobilienscout24 | Listing | Incapsula |

| Profile | In-house | |

| Leboncoin | Listing | DataDome |

| Lowe's | Product | Akamai |

| Nordstrom | Category | Shape |

| Shein | Product | In-house |

| Walmart | Product | PerimeterX + extra |

| YouTube | Transcript | In-house |

| Zillow | Listing | PerimeterX |

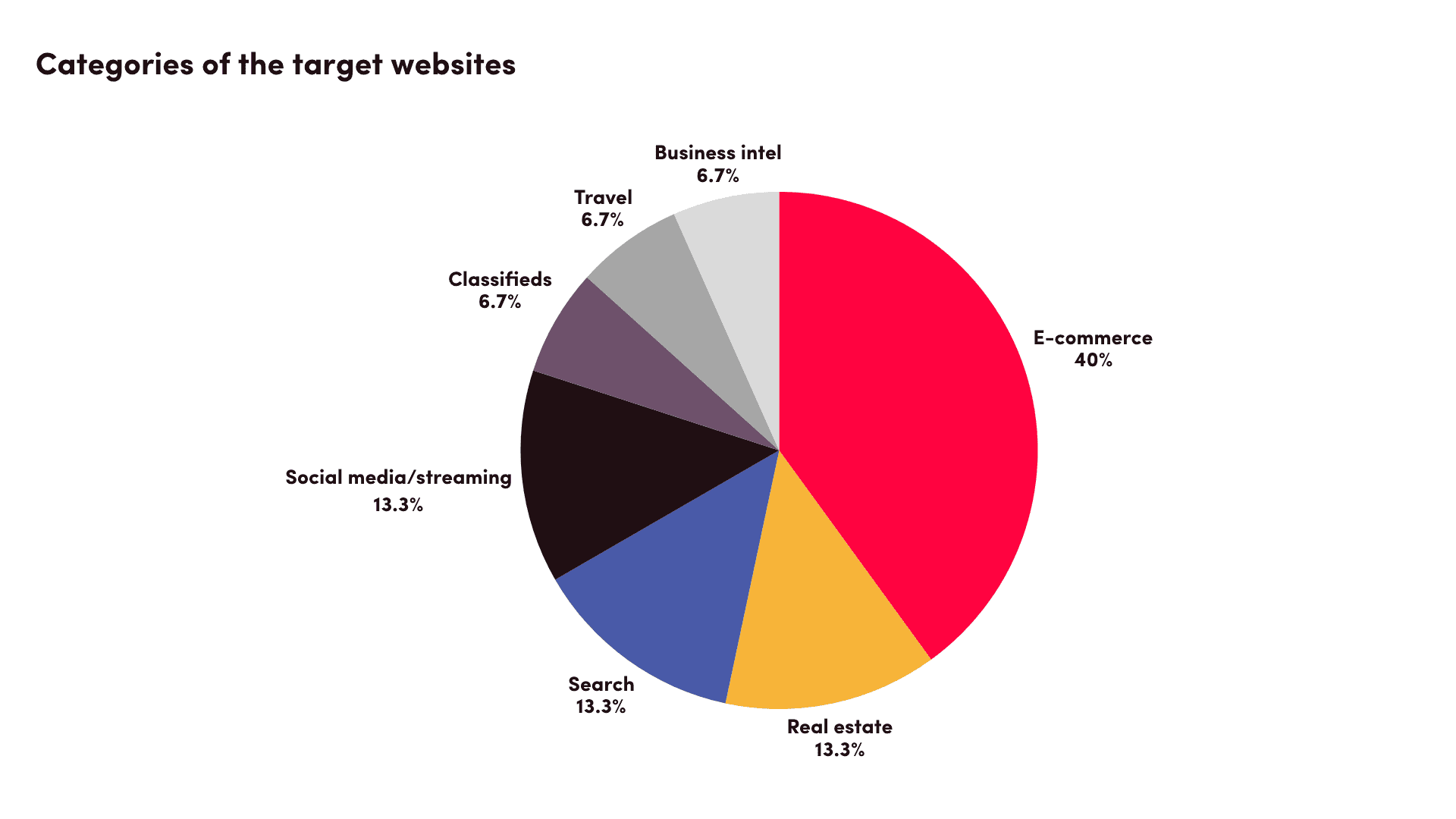

The selection skews toward e-commerce websites, though it really represents quite a few verticals:

- We collected ~6,000 unique URLs for each target website.

- We then wrote a basic Python script that would call the APIs and retrieve the output. If an API had special endpoints for websites, we used those.

- Our server was located in the US, and in most cases, we also set the geolocation of the APIs to the US.

- We figured out a working configuration with each target, starting from base parameters. For example, some targets required JavaScript or enabling premium proxies to return valuable content.

- We ran our script to fetch the 6,000 URLs twice: at 2 req/s and 10 req/s, with a timeout of 600s. This was enough to trigger bot protection systems – and sometimes hit the concurrency limits of the APIs.

- We validated the results by looking at the response code, page size, and page title. In some cases (such as with ChatGPT), we also fetched a CSS selector.

- Our ZenRows and Firecrawl plans had concurrency limits which caused some requests to fail at 10 req/s. This was mostly a problem with Zenrows, so the results may not represent its full capabilities.

- Anti-bot systems may have different levels of protection based on the website (or even categories of the same website), so they may not show up in full force against scraping of public web data.

- We tried opening the target websites at a similar time but couldn’t always guarantee perfect parity. While we maintain that an API should be able to access targets consistently, there’s always a chance to catch a scraper within its maintenance window between website updates.

- In the same vein, our benchmarks occurred in a limited timeframe, so they merely give a snapshot of API performance.

Benchmark Results

We excluded runs that succeeded under 5% of the time. And if an API couldn’t unblock a target at 2 req/s reliably, we didn’t try running 10 req/s.

Just to give you some context, two requests per second translate to just over five million per month, while 10 requests per second add up to nearly 26M monthly requests.

Aggregated results

(Hover on a label to highlight, click to hide)

Just like last year, Zyte did an amazing job at unblocking tough websites. Decodo, Oxylabs, and ScrapingBee found themselves close behind.

ZenRows and ScraperAPI also proved to be strong all-rounders, while the rest could be considered specialist providers in our context. Firecrawl placed last, but this API is best suited for crawling the long-tail rather than individual protected targets.

Target breakdown – 2 requests/second

(Hover on a label to highlight, click to hide.)

The graph is somewhat hard to parse (you can hide websites by clicking on their labels), but it shows which targets tripped the APIs. For example, Shein was a problem for most, while G2 proved too much to handle for Oxylabs, Decodo, and ScrapingBee – but not ScraperAPI.

Target breakdown – 10 requests/second

(Hover on a label to highlight, click to hide.)

Increasing the scraping speed five-fold had an impact, but it was smaller than we expected. ZenRows suffered the most, likely due to hitting concurrency limits.

Avg. response time of successful requests

(Hover on a label to highlight, click to hide)

We noticed that the response times were similar whether the script ran at 2 or 10 req/s – and sometimes even lower at the faster rate! Therefore, we decided to only show the results of the fastest successful run.

The response times between the APIs varied by a lot. Firecrawl took an interesting strategy of failing fast rather than repeating requests internally. It does work, but it offloads the burden of retrying to the user.

All things considered, Zyte was probably the fastest, followed by ScraperAPI, Decodo, and Oxylabs. Notice that all these providers also did well at unblocking the targets.

At a median response time of 5.05s (we’re using median due to one significant outlier), none of the APIs were adequate for agentic Google access. Granted, we didn’t use the so-called light or fast endpoints but rather the generic option.

Number of consecutive results per hour

(Hover on a label to highlight, click to hide)

Let’s try a different approach. How many successful results could we get if we sent requests consecutively, keeping one open connection? Compared to the previous graph, this accounts for the time consumed by failed requests.

The leaders remained similar. ZenRows and Nimble benefited thanks to YouTube, NetNut fell by several ranks, and Firecrawl flipped from the first position to being last.

Apify’s system is distinct enough to warrant its own section.

- First of all, it’s a marketplace of scrapers, many of which were made and are maintained by third parties.

- Second, the scrapers create a Docker container for each run; you’re free to assign them as much memory and CPU power as you need.

- Then, they take URLs in batches instead of looping through individual pages.

- And finally, you can only suggest concurrency – the platform often ignores this setting and adjusts it dynamically.

Apify – successful runs

| Actor used | Results | Runtime | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegro | Generic | 7,442 | 19m 19s | ~6.42 req/s |

| Amazon | Specialized | 5,946 | 3h 30min | ~0.47 req/s |

| G2 | Specialized | 5,926 | 14m 56s | ~6.6 req/s |

| Specialized | 6,000 | 28m 33s | ~3.5 req/s | |

| Specialized | 5,956 | 22m 42s | ~4.37 req/s | |

| Walmart | Specialized | 4993 | 14h 3m | ~0.01 req/s |

| YouTube | Specialized | 6,001 | 6h 12m | ~0.27 req/s |

| Zillow | Specialized | 5,998 | 12m 26s | ~8 req/s |

Some of Apify’s scrapers performed very well – G2 in particular. However, we had little control over their concurrency, resulting in wildly different runtimes.

For comparison, at 2 req/s, a run takes around 50 minutes, and at 10 req/s, it should end in roughly ten minutes.

Apify – failed runs

| Actor used | Results | Runtime | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT | Generic (custom Camoufox) | 4584 | 21h 10m | Stopped early |

| Hyatt | Generic (custom Camoufox) | 0 | 12m 4s | All requests failed |

| Immobilienscout | Generic (Playwright) | 4,145 | 16h 6m | Stopped early |

| Leboncoin | Specialized | 620 | 17h 44m | Stopped early |

| Lowe's | Specialized | 89 | 1h 27m | Stopped after 4 retries |

| Nordstrom | Specialized | 2,078 | 17h 32m | Stopped early |

| Shein | Generic | 541 | 11m | Finished without retrying |

Even when Apify had dedicated actors, they failed to work with around half of the targets. For example, the Shein scraper just looped through all URLs, got blocked, and didn’t even try to retry requests. Leboncoin, on the other hand, took way too long to complete, so we had to abort the run.

Hardest Targets to Unblock

| Avg. success rate at 2 req/s | APIs with over 80% failure | |

|---|---|---|

| Shein | 21.88% | 5 |

| G2 | 36.63% | 5 |

| Hyatt | 43.75% | 5 |

| Lowes | 52.57% | 4 |

| 59.54% | 3 | |

| Nordstrom | 61.97% | 3 |

| Leboncoin | 63.83% | 3 |

| Allegro | 66.98% | 2 |

| ChatGPT | 71.04% | 1 |

| Immobilienscout | 71.68% | 1 |

| YouTube | 93.05% | 0 |

| Walmart | 93.05% | 0 |

| Amazon | 93.30% | 0 |

| 94.78% | 0 | |

| Zillow | 97.85% | 0 |

At least in 2025, Shein is where web scraping dreams die. Very few APIs were able to open it at all, let alone reliably. In addition to having huge page sizes when downloading the HTML, this target is very well protected.

G2, which now uses DataDome, proved to be another headache. Guarded by Kasada, Hyatt was the third.

The most popular web scraping targets, Google and Amazon, painted another story. The main concern here wasn’t if the APIs will open these targets, but rather how fast. Had we tested data parsing capabilities, this would have been another point of relevance.

Cost to Run Our Tests

Assuming we made 14,000 requests per target (6,000 x 2 + 2,000 for leeway), how much did it cost us?

Hover on a label to highlight, click to filter.

Surprisingly, the providers that performed the best were also the most financially viable options. Decodo and Oxylabs benefitted from their relatively flat pricing structures which have seen at least one price cut since last year.

Zyte was among the cheapest providers with many of the targets (our 14,000 YouTube requests cost just $1!), but it also scaled by orders of magnitude when tougher protection mechanisms or headless browsing got involved. G2 and Hyatt alone consumed over a half of our budget.

While affordable in regular scenarios, providers with credit-based models like ScraperAPI and ScrapingBee are evidently not ideal for opening protected websites. Zenrows, however, has lower caps and thus compares better.

Apify is once again the odd duck. Its individual scrapers may have different pricing models (traffic/compute/requests), add-ons, and even subscription fees for access. For example, the Walmart scraper charges $30/mo just for getting to use it. As such, some of the scrapers – like G2 or Instagram – were very affordable, while Leboncoin ate over $60 for returning one tenth of the results.

Base and Most Expensive Rates

Our calculations are unlikely to represent real usage scenarios, as few users target exclusively protected websites. Here are the cheapest and costliest rates per 1,000 requests (CPM) at the arbitrary budget of $500.

Hover on a label to highlight, click to filter.

The graph reveals a huge gap with some of the APIs. For example, Zyte costs peanuts for basic targets but charges a premium for the toughest websites. So do ScraperAPI and ScrapingBee.

The latter two have relatively defined credit schemes, but Zyte makes it challenging to understand your expenses upfront. While there is a handy calculator, the provider segments websites into five buckets; the rates further react to volume discounts, rendering, and parsing options.

Compared to 2024, we’re seeing more segmentation in pricing models. Oxylabs has introduced separate rates for rendered requests, Amazon, and Google. Crawlbase has added Zyte-like difficulty tiers and even calculates volume discounts separately for each.

Narrative of the Year: AI

Artificial intelligence – more specifically, large language models – has been sucking all air out of the room for what, two years now? The web scraping industry experiences this especially acutely, as data (either datasets or real-time web content) underlies AI training and interactions with the web. Basically, we’re selling shovels during a gold rush.

Given how important the relatively obscure niche of web data collection has become, the word of the year is attention – whether we’re talking about the business, product, or even legal side of things. Let’s dissect some of the ways this state of affairs has transformed our industry.

Unprecedented Influx of Venture Capital

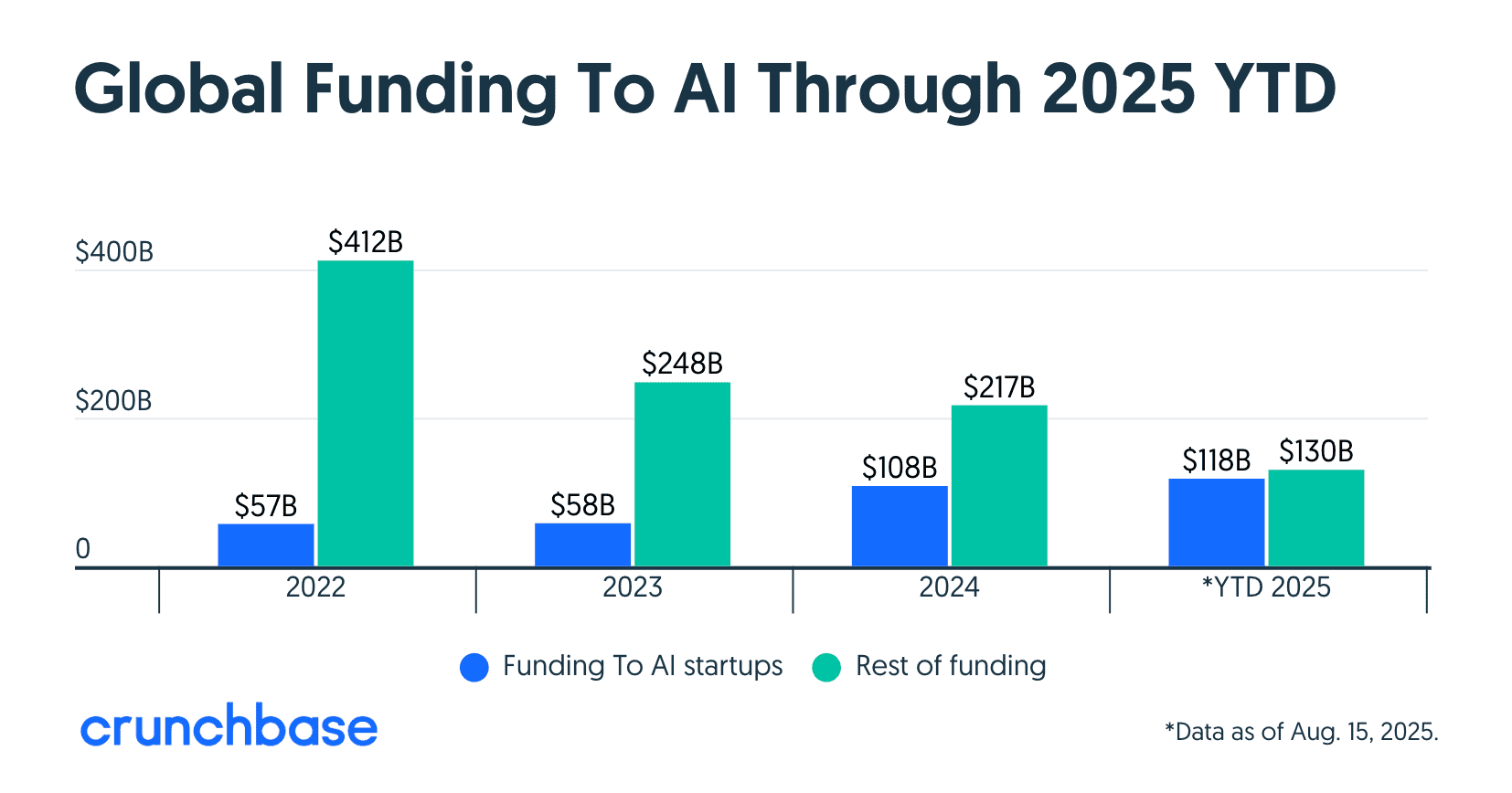

How do you quantify hype? It’s simple: just follow the flow of venture capital. In this case, the numbers are more than obvious: in 2024, AI startups received twice as much funding than the year before; by August 2025, they had already raised more than in 2024 as a whole. Out of total VC investments this year, AI had raked nearly a half of the pie, compared to just one third the year before.

Much of this money went to several largest companies in the field, such as the $40 billion investment into OpenAI. While miniscule in comparison, over $150 million were allocated to startups in the area of web data access. The only other big VC investment event in this market has seen (or at least, we’ve seen) involved EMK Capital’s $100M+ acquisition of Bright Data – back in 2017!

| Company | Founded | Headquarters | Funding (2024-2025) |

| Exa.ai | 2021 | California, US | $85M |

| Browserbase | 2024 | California, US | $67.5M |

| Tavily | 2024 | New York, US | $25M |

| OnKernel | 2025 | Delaware, US | $22M |

| Browser-Use | 2024 | California, US | $17M |

| Firecrawl | 2024 | Delaware, US | $14.5M |

The investees are all based in the United States, with an average age of under two years. American companies have always participated in this industry, though never really as dominant players. But now, venture capital has effectively spurred a new generation of well-equipped web scraping infrastructure providers.

New Generation of AI Web Scraping Companies

Let’s talk about this new generation. Does it have any defining characteristics to distinguish it from the old guard, or are we getting more of the same? In brief, these companies are different, both in features and mindset.

The focus areas of gen-AI web scraping companies

| LLM-friendly scraping | Web search (Google, in-house, mixed index) | Browser agents |

| Firecrawl Crawl4AI ScrapeGraphAI | Exa Tavily Perplexity | Browserbase Browser-Use OnKernel |

First, they are AI-native businesses, which is obvious looking at the marketing. Firecrawl offers to “turn websites into LLM-friendly data”, Browserbase promises “a web browser for your AI”, and Tavily entices to “connect your {AI} agent to the web”. There’s no question who the desired user is, or how this user can benefit from the service. Quoting Tavily’s CEO, these companies first and foremost identify themselves as AI enablers.

Gen-AI’s approach also differs when it comes to the product. For one, they love to simplify input by either directly accepting natural language or building abstractions that do. As an example, Browserbase’s Stagehand library gives users the choice when to use code or plain language instructions to automate a browser. The later-released Director goes a step further and expects only plain language commands.

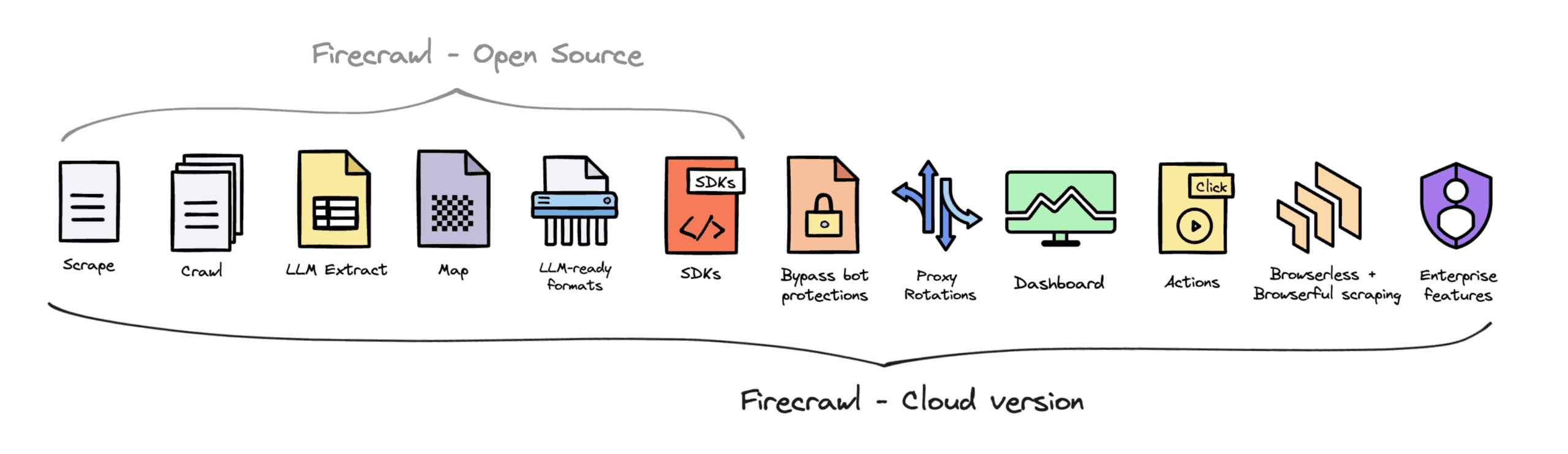

Furthermore, gen-AI pays particular attention to website crawling, which web scraping infrastructure providers traditionally avoided. Now, it’s easier than ever to fetch the URL structure or complete contents of a website; all you need to do is call an endpoint and tweak a few knobs.

In the same way, you can request to scrape not only the list of Google’s search results but also their content. The addition of Markdown formatting makes wholesale crawling directly useful for language models. Exa and Tavily go a step further: instead of simply scraping Google, they cache, interpret, and repackage results to replace the search engine for AI agents.

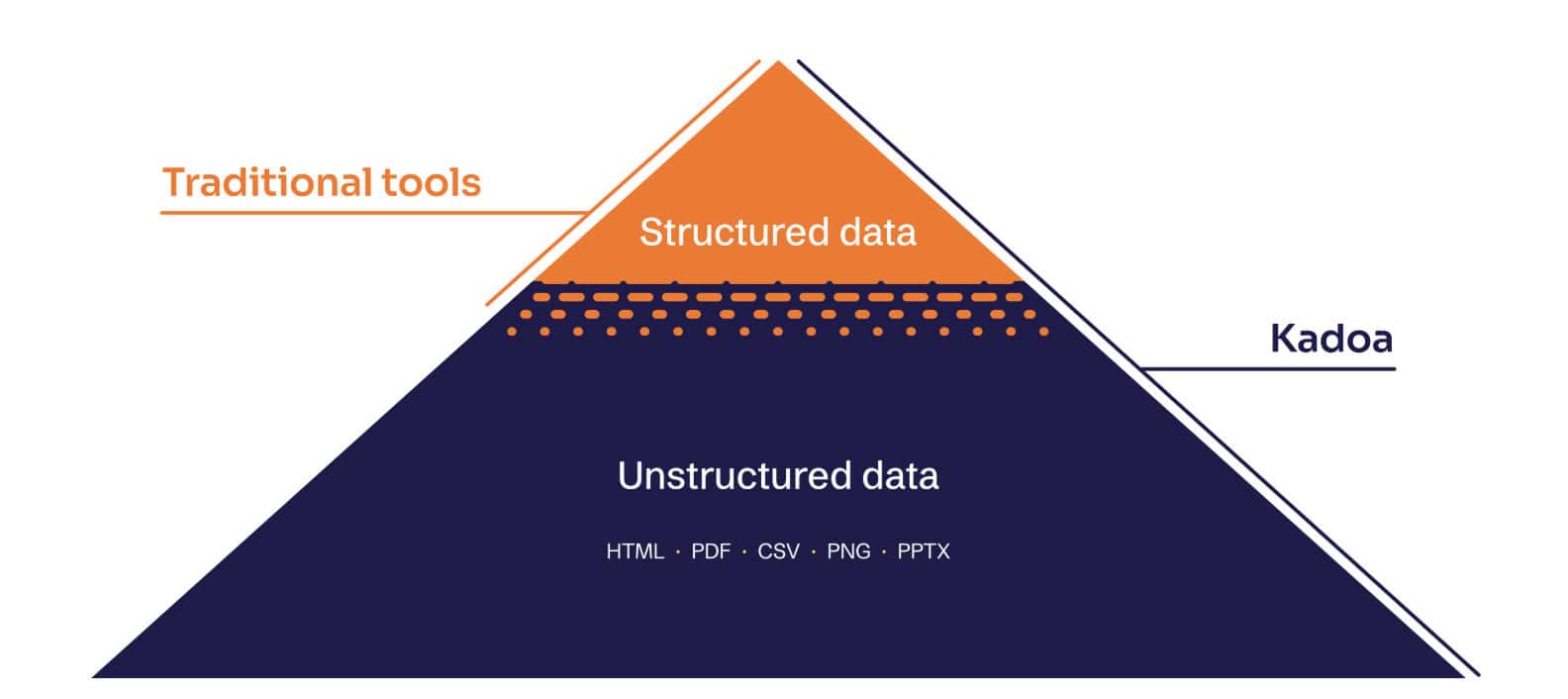

Gen-AI providers themselves make heavy use of LLMs in data processing. Machine-generated static parsers for humans are relatively rigid; human-specified parsing rules for AI, on the other hand, work decently well – and, more importantly, transfer between domains without breaking too much. This unlocks what Zyte calls the long-tail of the web and marks a big step in scalability over handcrafted parsing rules.

The final, though probably least quantifiable, characteristic is the mindset. While they foremost offer infrastructure, the new crop seem to have a builder’s mentality. They show no qualms over layering research assistants, lead enrichment agents, and other functionality upon the core service. This showcases the platform’s capabilities, expands the problem space, and creates potential opportunities for a pivot.

In contrast, incumbents have clearly-defined domains and focus on solving engineering challenges within them. As such, their approach is often iterative and oriented toward maintaining rather than creating. This results in less hype but more solid backbones. And, of course, without impatient venture capital firms breathing down their necks, there’s less external pressure to gun for moonshots.

Emergence of Powerful Open-Source Tools

An interesting corollary of the builder mindset is the attention shown to open source. Apify and Zyte have created amazing web scraping frameworks (Crawlee and Scrapy, respectively). But these two examples aside, most of the open tooling has come from individual developers giving rather than businesses giving back to the community.

Things changed in 2024. The gen-AI scraping companies made multiple GitHub repositories that, in the least hyperbolical sense of the word, have exploded in popularity:

| Repository | Purpose | GitHub stars (Sep ’25) | License |

| Browser-Use | Manipulation of headless browsers | 70K | MIT |

| Firecrawl | Crawling, scraping & data parsing | 60K | AGPL-3 |

| Crawl4AI | Crawling, scraping & data parsing | 54K | Apache-2.0 |

| GTP Researcher (Tavily) | Creating deep research agents | 23.5K | Apache-2.0 |

| Stagehand (Browserbase) | Manipulation of headless browsers | 17K | MIT |

There are two things to highlight about this phenomenon. The first is that the community didn’t just get a bone with useful but ultimately minor functionality, such as simulating mouse movements. Crawl4AI is a complete and fully open-sourced web scraper. Firecrawl and Browser-Use, in turn, run an open-core business model which monetizes cloud hosting, anti-bot avoidance, and quality-of-life features.

The second striking observation is that all but one of the listed repositories enforce highly permissive licensing models. In essence, only Firecrawl limits redistribution, requiring adopters to share any changes they make to the code.

Where’s the value for the company? Well, open-core can be a viable business model in its own right, as exemplified by RedHat. But really, it’s an amazing approach for building mindshare, and for gradually moving businesses to the managed service once they encounter the hairy areas of web scraping.

Adaptation of the Incumbents

How has the AI boom affected the so-called establishment of web data providers? Some embraced it like their only newborn; others, conversely, have made few changes that cut beyond skin deep. In any case, most have acknowledged the importance of large language models in their businesses.

The first and most obvious area to embrace AI was marketing. Early birds like Apify and Bright Data started courting startups by the end of 2024. First, the efforts were modest: a section in the navigation bar, a landing page, or a banner. By March 2025, Bright Data had completely pivoted to serving AI use cases, reducing other clients to everything else and then simply BI in its headline.

The gambit seems to have paid off: in late 2025, Bright Data announced that AI enabled it to hit $300M per year (up from $100M in 2021), and that it expected to reach $400M ARR by mid-2026.

Others followed suit throughout 2025. Apify now provides real-time data for your AI, NetNut powers AI models (in bold) & complex pipelines, Oxylabs’ products empower the AI industry and beyond, while SOAX offers real-time public web data for AI teams. Not all had converted when we wrote this, though: ScraperAPI, Zenrows, and even Zyte remained modest about wooing AI companies.

Web scraping APIs are a natural match for large language models. But the peculiar needs they bring, such as limited context sizes or their hunger for Google search data, also required implementing new features. The list includes Markdown, plain text, or Toon output formats, lightweight versions of Google parsers, and lately MCP servers for agentic browsing.

In addition, the AI craze gave impetus for launching new products to wrestle with emerging competitors. For example, Bright Data made a crawling API and spun off its cloud browsers into a new, AI-first brand browser.ai. In its own right, Oxylabs announced an unblocker browser service, and it runs a separate suite of Firecrawl-like scrapers called AI Studio.

Comparison of AI-oriented features

| Discovery endpoints | Search endpoints | Browser endpoints | Structured data | Output formats | MCP server | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apify | Crawler, mapper, target-specific | SERP APIs | ❌ | Target-specific | HTML, JSON, CSV, Markdown, | ✅ |

| Crawlbase | Target-specific | SERP APIs | ❌ | Target-specific | HTML, JSON, screenshot | ✅ |

| Decodo | Target-specific | SERP APIs | ❌ | AI selector generator, target-specific | HTML, JSON, Markdown, screenshot | ✅ |

| NetNut | ❌ | SERP APIs | ❌ | Target-specific | HTML, JSON | ❌ |

| Nimble | Target-specific | SERP APIs | ❌ | Target-specific, AI parser | HTML, JSON, screenshot | ✅ |

| Oxylabs | Crawler, mapper, target-specific | SERP APIs, fast search, search + extract | ✅ | Target-specific, AI selector generator, AI parser | HTML, JSON, Markdown, screenshot, Toon | ✅ |

| Scrapeless | Crawler, target-specific | SERP APIs | ✅ | Target-specific | HTML, JSON, text, Markdown, page content | ✅ |

| ScraperAPI | Crawler (beta), target-specific | SERP APIs | ❌ | Target-specific | HTML, JSON, text, Markdown, screenshot | ✅ |

| ScrapingBee | Target-specific | SERP APIs | ❌ | Target-specific, AI parser | HTML, JSON, text, Markdown, screenshot | ✅ |

| ZenRows | Target-specific | SERP APIs | ✅ | Target-specific, output filters (links emails, etc.) | HTML, JSON, Markdown, text | ❌ |

| Zyte | Products, articles, jobs | SERP API | Through hosted VS Code | Page types (products, articles, jobs, SERP) | HTML, JSON, page content | ❌ |

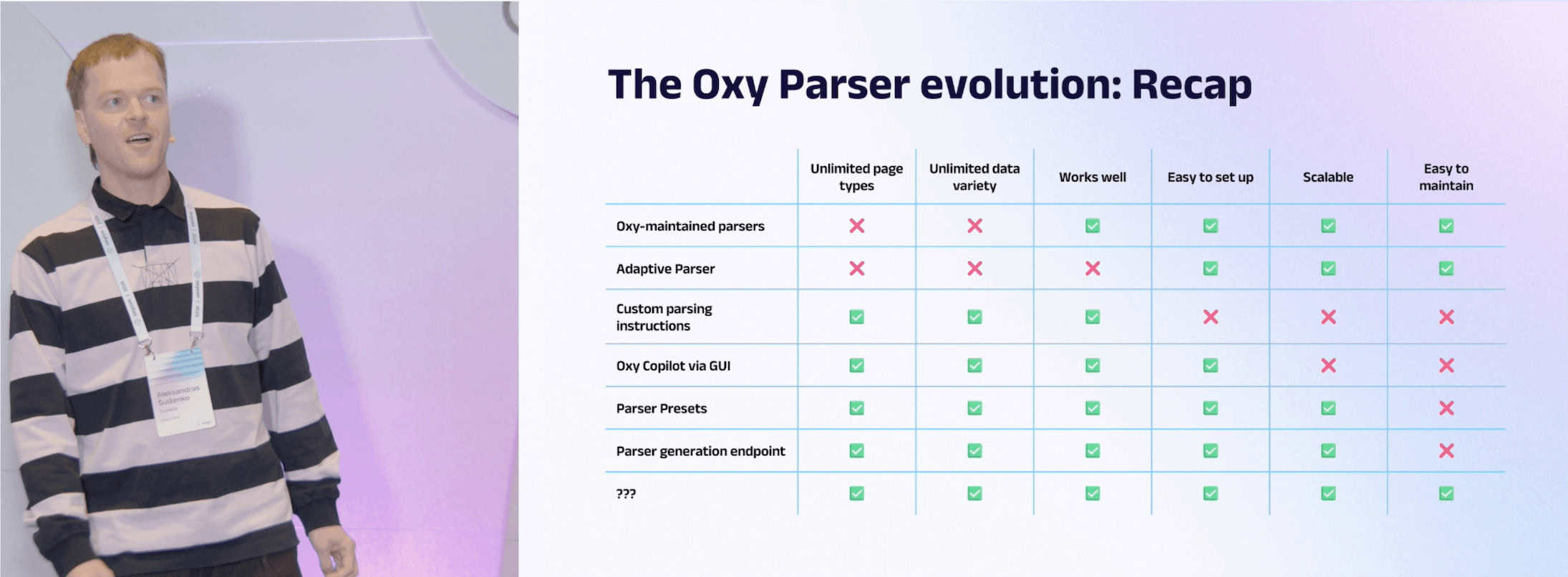

The same models that rely on web scraping to improve have found themselves in the list of scraper API features, creating an interesting synergy. Their main customer-facing role lies in data transformation: either by generating parsing rules from a prompt, or the other way around – extracting data directly with the rules given to them. This slide from OxyCon shows the winding path established providers take in adopting AI for parsing:

Even then, few of the entrenched providers have introduced agentic web scraping that could extract information end-to-end using a prompt. This, and the more modest task of LLM parsing in general, are hardly enterprise-ready in reliability and cost, so they compete with other methods for structuring the long-tail of the web.

The most active in this domain is probably Zyte, whose machine learning models are able to extract various page types (product, news, etc.) in predictable schemas. Some others have implemented it as well, such as Scrapfly. But this method has received limited adoption in general.

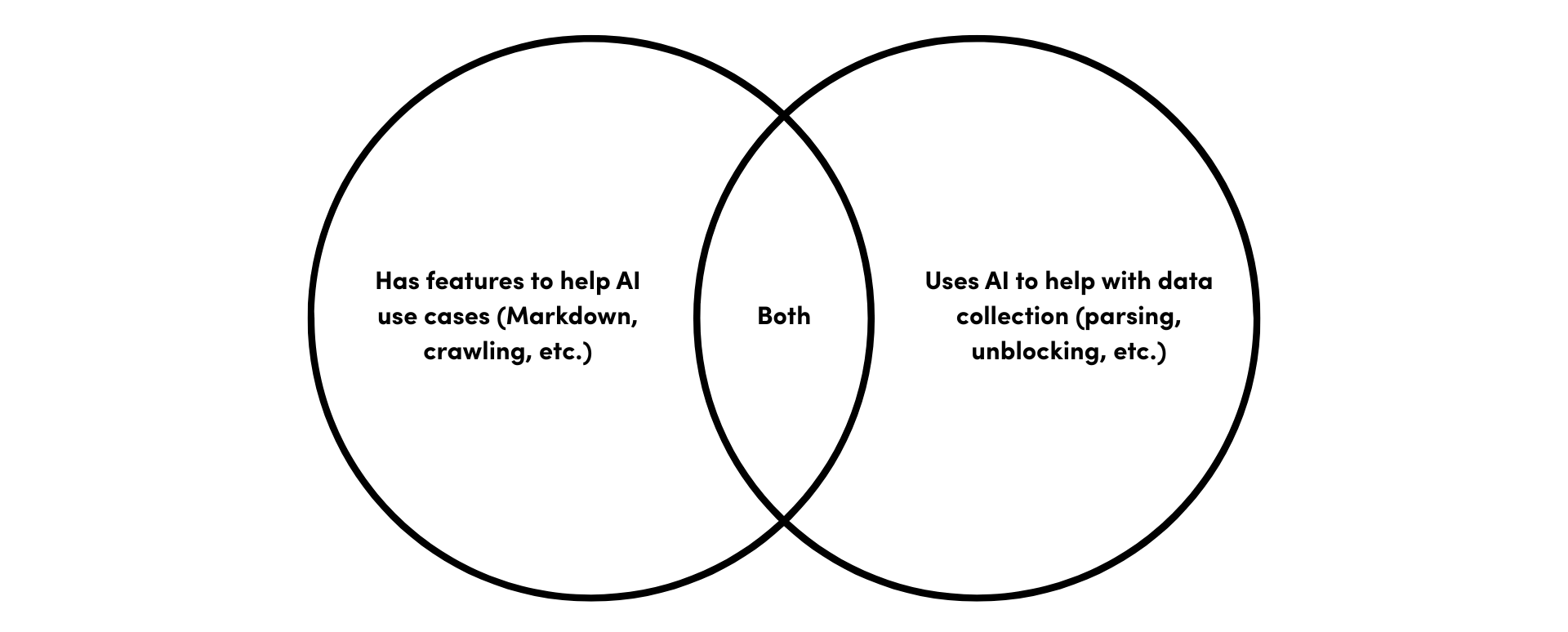

AI-oriented and regular web scrapers can be distinct enough to warrant putting them into separate taxonomies. But this is where we, as reviewers, encounter head-scratching problems. Is an AI web scraper something that helps AI use cases or implements AI to function better? Maybe the answer lies somewhere in-between.

Multimodal Data (and Training Data in General) Remain in Big Demand

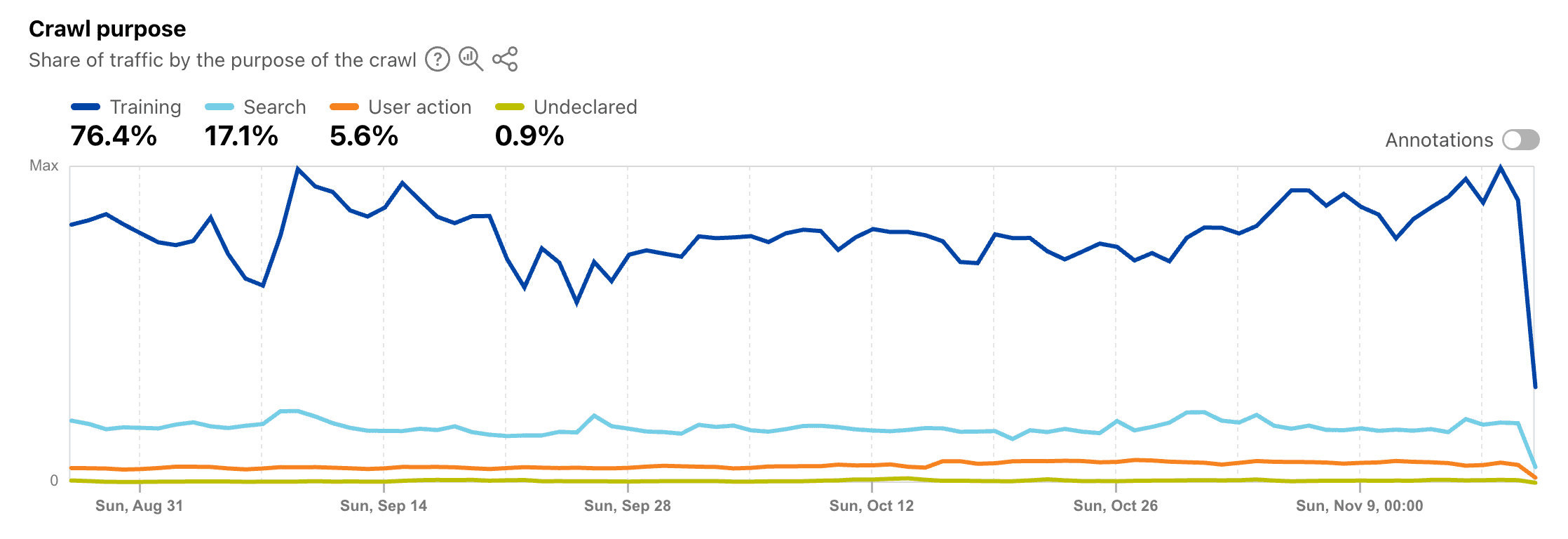

With the hype cycle around LLMs shifting to RAG and then agents, you’d think that the web as a source of training data has been exhausted. Indeed, some have turned to synthetic, user-generated, and licensed data to improve inputs. But according to Cloudflare, that’s not the case: three quarters of all AI traffic in mid-2025 were generated for training purposes.

Of course, it would be unwise to treat this matter as either-or. As always, the answer requires more nuance. Textual web data for training purposes, while foundational, has indeed become less relevant and extracted many times over. It may also be starting to suffer from recursion, where an LLM ingests content generated by another AI model. Multimodal data like videos, however, remains the frontier for further training. We wrote about it back in spring, and we still believe it to be the case.

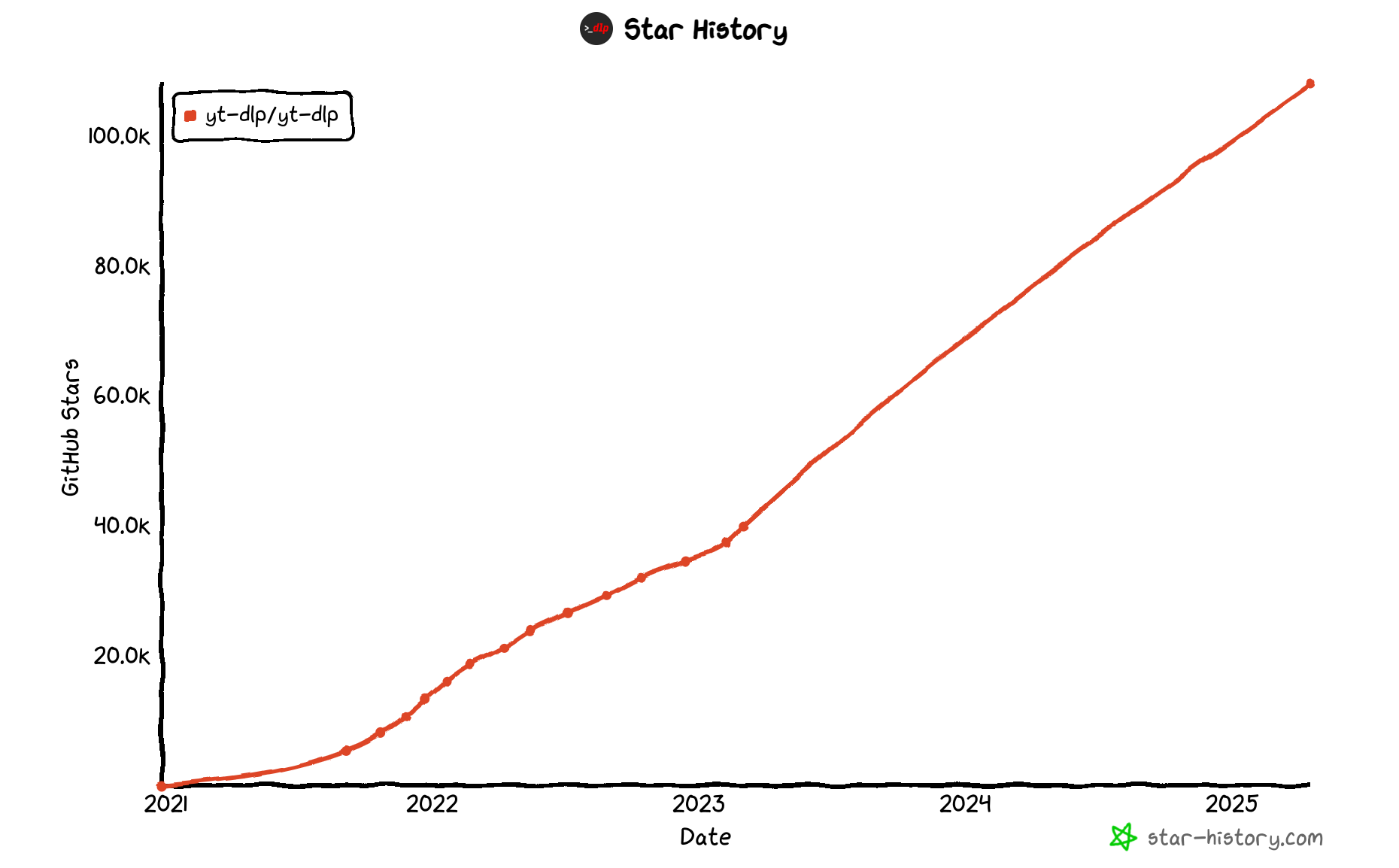

To reinforce our point, we’ll once again whip out the GitHub trendline of yt-dlp, a popular library for downloading videos. What’s different today is that the market now also offers a choice of commercial scrapers and pre-collected datasets. Oxylabs and Wyndlabs are just some examples of providers that are capitalizing on this opportunity.

If we take Cloudflare’s graph as ground truth, agentic scraping has generated more talk than action so far. However, with the way things – and funds – are going, its share is bound to grow.

Intensifying Efforts to Curb Data Collection for AI

More attention to web scraping has brought its fair share of negative consequences. Companies have never been keen on giving unfettered access to their data, whether to keep a competitive edge or to avoid unnecessary hosting expenses. But now, in addition to reaching an unprecedented scale, web scraping has started threatening established business models.

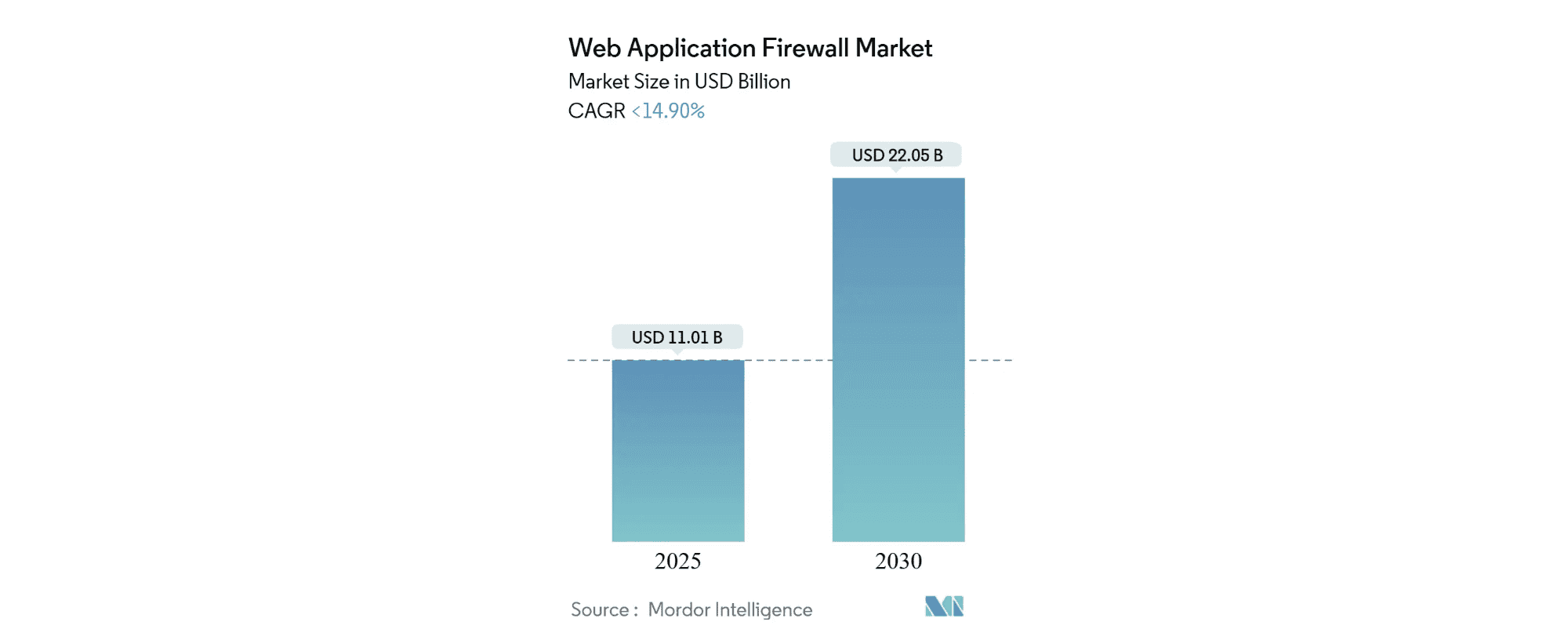

Should we believe an insights company called Mordor Intelligence, the market for Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) is at $11 billion. Akamai alone makes nearly $4 billion per year, and we’ve seen some high-profile mergers and acquisitions, such as the ten-figure acquisition of Shape Security by F5, or the merger between PerimeterX and Human.

The general sentiment in major web scraping conferences like OxyCon and Extract Summit is that anti-bot efforts have toughened significantly. One participant half-jokingly shared that two days of unblocking efforts used to give two weeks of access to websites; now, it’s become the other way around. Zyte went as far as to proclaim the death of proxies, arguing that there’s no longer sense or skill for many to build a web scraper in-house.

Bot detection services can still cost a lot. But they’re becoming both more advanced and more accessible for businesses. Many smaller websites find Cloudflare’s ubiquitous “are you human?” checkbox good enough, and this feature comes for free.

Even the web giants which were always challenging but reasonable to scrape are bristling up. The case in point is Google: in January, it sent the industry into chaos by starting to require JavaScript in Search. In September, it stopped returning 100 search results in one request, breaking many SEO tracking tools. YouTube has also been affected: it may require solving a CAPTCHA before playing a video or straight out refuse to do so until the suspicious user logs in.

Cloudflare and its various AI-focused initiatives warrant a separate mention. In 2025, Cloudflare’s users received the option to trap AI crawlers in a labyrinth, then to block them altogether. The company didn’t stop here: it undertook to control access by first launching a bot authentication protocol and then an option to pay for crawling through the use of 402, a forgotten HTTP response code. These audacious moves both promote cryptocurrency (which is used to pay for access) and try to redefine the web’s incentive system.

Cloudflare’s efforts have received mixed reception. The new crop of web scrapers like Browserbase and Browser-Use actually jumped at the opportunity, integrating web bot auth and pay-per-crawl into their systems. Entrenched providers like Bright Data saw this as an affront against the open web and an attempt to become a gatekeeper. We tend to lean towards the latter position.

Conclusion

This concludes the report – thanks for reading! Since the summary is at the front, we’ll use this opportunity to invite you to ask questions or give feedback. Feel free to reach out through info at proxyway dot com or our Discord server.