Internet Sharing SDKs: a Closer Look at the Emerging App Monetization Method

Once, sharing your internet meant handing over the Wi-Fi password. These days, it might mean turning a slice of unused bandwidth into passive revenue. The idea sounds promising, but it also raises fair questions. What’s really being shared? Who’s profiting? And most importantly, is it safe? That’s why we decided to chime in and look at how internet sharing SDKs are reshaping app monetization.

What Is an Internet Sharing SDK

An internet sharing SDK (Software Development Kit) is a lightweight component integrated into mobile, desktop, TV apps, or even browser extensions, letting users voluntarily share small portions of their unused internet connection with approved third parties. In return, developers earn passive income – without showing more ads, selling upgrades, or begging for subscriptions.

Instead of routing traffic through traditional data center servers – which can be flagged or blocked due to their non-residential nature – these SDKs rely on real user devices. The connection is opt-in, and the user’s IP address becomes part of a larger distributed network used by businesses for legitimate use cases.

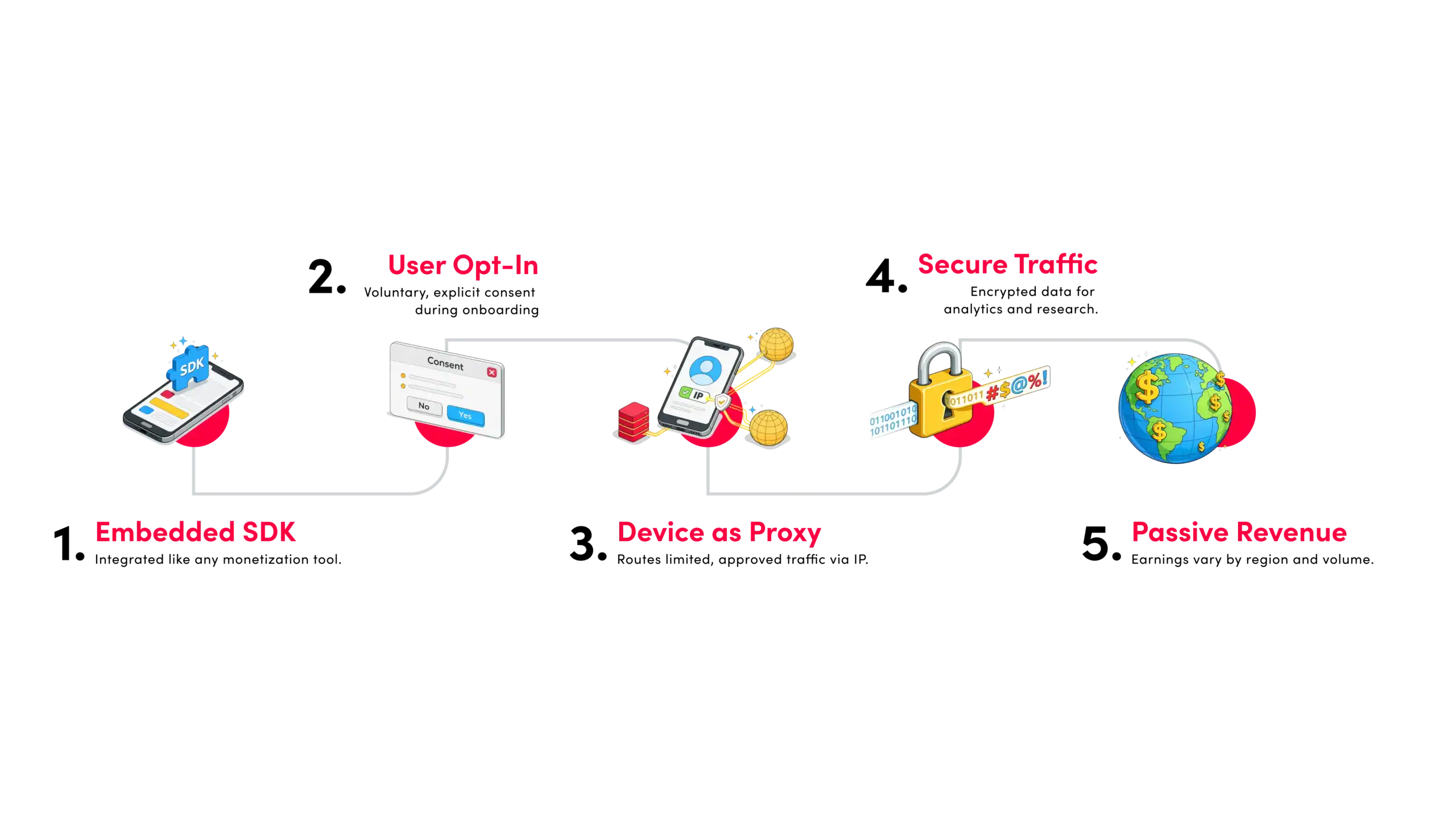

Here’s how it typically works:

- The SDK is embedded directly into the app, just like any other monetization or analytics component.

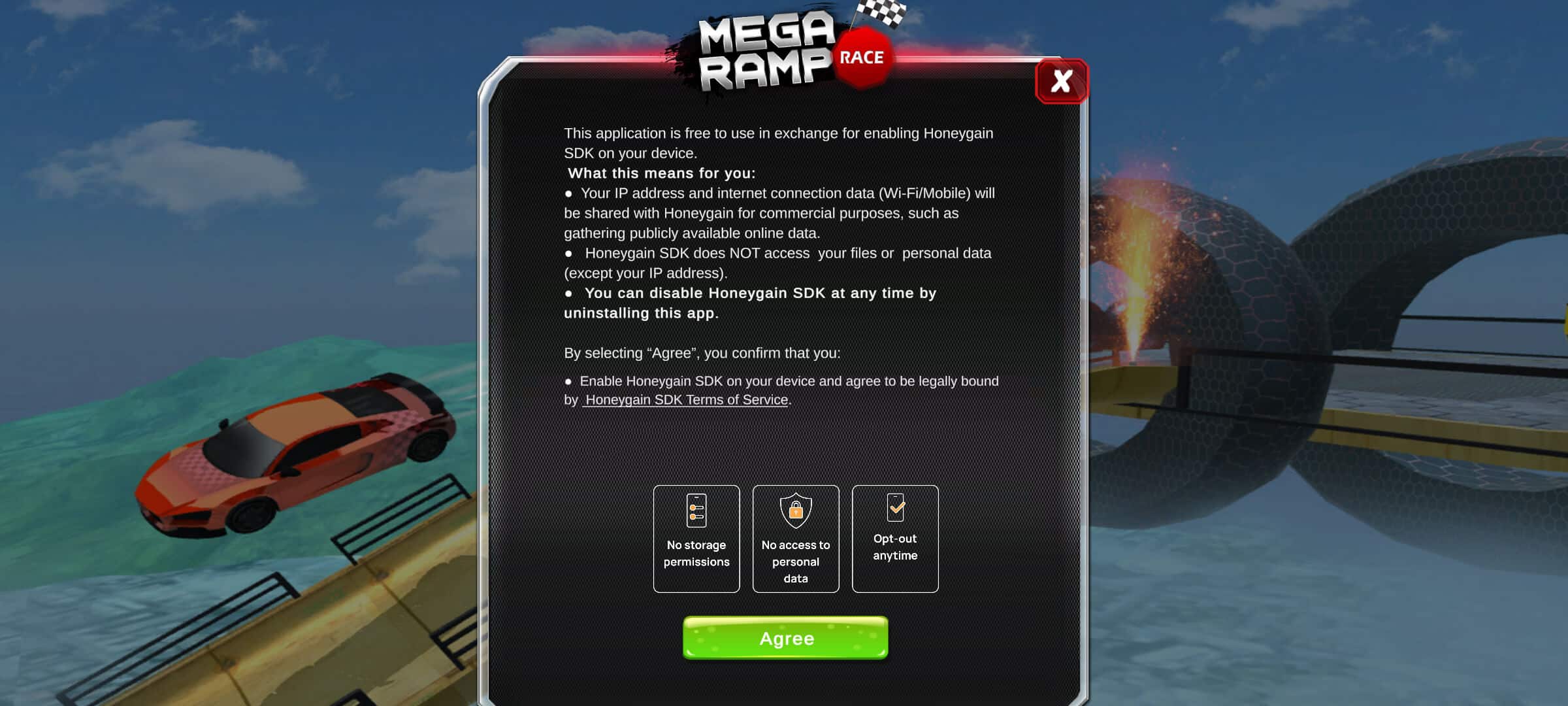

- Users opt in voluntarily, usually during onboarding or when unlocking features like premium access, rewards, or ad-free experiences. In GDPR-compliant regions, this consent must be explicit and informed.

- A certain amount of approved traffic is routed through the user’s device, borrowing their IP address. Effectively, the user turns into a proxy.

- All traffic is anonymized, encrypted, and used by businesses for tasks like SEO monitoring, ad fraud detection, competitive analysis, and market research.

- Developers earn passive income based on geography and usage volume, often calculated using CPM-style payouts. Top rates range from ~$0.001–$0.03 per user per day or up to $30 per 1,000 Daily Active Users, depending on region and provider.*

*These figures reflect published rates as of 2024-2025; actual developer earnings will vary by app usage and user base demographics.

Where Are the Internet Sharing SDKs Used?

Utilities like Free Snipping Tool offer users premium features in exchange for opting into SDK. The integration is transparent and opt-out is available. Media and Streaming Apps, such as Megacubo, bundle SDK to unlock extras like screen recording – again, only after user opt-in.

Crowdfunding Platforms like CareBuzz leverage SDK to convert shared bandwidth into charitable donations, turning the model into a non-cash incentive. Smart TV and Puzzle Games using SDK show how passive monetization can boost ARPDAU (average revenue per daily active user) in long-session, low-engagement formats.

Why Developers Are Considering Internet Sharing SDKs?

Internet sharing SDKs don’t sell clicks, show banners, or unlock loot boxes. So why are they showing up in monetization stacks? The short answer: they shift the model. Instead of charging for attention or conversion, they monetize presence.

It’s no surprise the model first gained traction in VPNs, utility tools, and desktop software – categories where users are already familiar with trading idle resources for perks. But there’s more to it:

- Monetizing passive users. Clicking on ads or making a purchase is not what most users do, but they still use app resources. Internet sharing SDKs provide a way to generate income from that passive usage. Rather than increasing engagement, they offer value in the background.

- Low implementation overhead. Integration time is short, typically 1–2 days, and there’s little need for ongoing optimization. Unlike ads, which require testing placements, formats, and timing, or IAPs that demand balancing user incentives, SDK monetization tends to be plug-and-observe.

- Good earning potential. Some SDK providers offer revenue based on CPM-like models – meaning developers are paid a fixed amount per 1,000 active users or sessions, similar to how ad impressions are monetized. Rates can range from $1.50 to $6.00 per 1,000 daily active users, or $10–$70 per 1,000 unique IPs per month in high-demand regions. These are top-end figures – real-world earnings depend heavily on geography, user engagement, and session quality.

- Could be part of a hybrid monetization model. Unlike ads or subscriptions, internet sharing SDKs don’t cannibalize existing revenue channels. They operate in parallel, making them a common choice for hybrid monetization strategies.

- Works across device categories. These SDKs can be integrated into Android, iOS, Mac, Windows software, Smart TV apps – categories where other monetization models might underperform.

That doesn’t make this model superior, or right for everyone. But it helps explain why, over the past few years, more developers have begun quietly testing it – especially in apps with large user bases and limited direct revenue per user.

Back to the Roots: From Proxies to Monetization

To understand the need for bandwidth sharing SDKs, you may want to learn where this monetization method really comes from. It all started with good old proxies. Back in the 2000s, if you wanted to dodge a geo-block or test a website from another country, using proxy servers was often the best way.

By the early 2010s, companies increasingly realized proxies weren’t just for anonymous browsing – they could be used at scale to enable business use cases. By routing traffic through actual residential connections, businesses could test how ads are rendered across different countries, audit local search results, or simply overcome toughening website restrictions. This shift gave rise to residential proxies as a commercial tool.

Running these networks at a global scale was expensive. You needed thousands of residential devices, which couldn’t just be bought in bulk like datacenter-based IPs. Around 2013 Hola VPN appeared with what looked like a clever shortcut: it created a peer-to-peer network where users’ devices acted as access points for each other. In exchange, they got free VPN access – unknowingly powering the network themselves.

All was smooth until 2015, when it was discovered that Hola was also reselling its users’ bandwidth through a commercial branch, Luminati Networks, without user knowledge. The fallout prompted one of the first wake-up calls around user transparency. At the same time, new privacy laws were reshaping how the data was being used.

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) took effect in 2018, requiring organisations to obtain explicit user consent and improve transparency. In the US, California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) followed soon after, pushing companies toward the same standards nationwide. The message was clear: earn user trust or lose access.

That shift cleared the path for user-first platforms like Honeygain or Pawns.app, where people opted in to share some of their unused bandwidth and got paid for it. It was the same concept that once caused outrage – this time rebuilt on transparency and consent. Internet sharing had finally gone legit.

Not long after, the model branched out, turning its focus to developers and app publishers. Instead of building entire apps around bandwidth sharing, some companies started packaging the functionality into modular SDKs. The underlying principle remains the same, but SDK creators now give much more attention to ensuring more transparency and safer use. While bandwidth-sharing SDKs remain low key – and sometimes carrying a stigma from the earlier days of misuse – they’re becoming a legitimate alternative to dominant monetization methods.

So before evaluating whether that stack holds up, it’s worth revisiting how the current monetization pillars (ads, IAPs, subscriptions) actually perform today.

How Internet Sharing SDKs Compare to Prevalent Monetization Methods

Most app developers lean on the same three monetization methods: ads, in-app purchases (IAPs), and subscriptions. They’re easy to implement, scalable across geographies and long time. However, they’re also fraught with issues that negatively affect user experience on the app.

Advertising is the classic default: show a banner, interstitial, or rewarded video, and you get paid when users see or click. The payout is usually measured by eCPM (effective cost per thousand impressions). However, since Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) policy rolled out in 2021, iOS ad performance has taken a serious hit. By some estimates, eCPMs dropped nearly 50% as advertisers lost access to user-level identifiers, such as device IDs and behavioral profiles, that enabled personalized targeting.

Ads still work, especially in large-scale apps and Tier-1 markets. But between shrinking margins, seasonality, and shifts in targeting accuracy, ad revenue has become increasingly volatile – making it harder to forecast or rely on consistently. Relying on this model alone is like balancing on a one-legged stool – possible but bound to topple.

In-app purchases (IAPs) offer direct monetization from engaged users. For example, in games, this means buying extra lives, virtual currency, or cosmetic upgrades. The revenue can be massive – according to Sensor Tower, IAPs generated $150 billion in 2024. That makes it the highest-earning app monetization method by revenue, even if it relies on a small pool of spenders.

On the other hand, it has been found that only around 5% of users spend money, and conversion rates in emerging markets are even lower. That means most of your audience contributes nothing financially, even if they open the app daily.

Meanwhile, internet sharing SDKs entered the game by making it possible to earn from the 95% who never hit “buy” – not by converting them, but by letting their devices do the contributing. The opt-in model preserves user choice but broadens the revenue base beyond power users.

Last but not least, subscriptions offer recurring access in exchange for monthly or yearly fees, a model popularized by media, productivity, and fitness apps. The data from Statista reveals that subscription-based apps made approximately $45.6 billion in 2023, a sizable share of the market.

But retention remains the Achilles’ heel. According to the RevenueCat report, nearly 30% of annual subscriptions are canceled within the first month, and over 40% of users say they’re tired of managing multiple app subscriptions. The fatigue and hesitance to pay for casual use has made long-term retention increasingly difficult.

As we mentioned previously, internet sharing SDKs offer a less intrusive option. Users can opt in once, change their minds later, and still contribute in the meantime.

Feature | Internet Sharing SDKs | In-App Purchases (IAPs) | Subscriptions | Ads |

Revenue model | Bandwidth/active users | Purchases by users | Recurring payments | Impressions / clicks |

Monethisation method | Opt-in once | Active spending | Long-term app usage | Engagement with the app |

Ongoing management | Low (monitoring opt-in only) | High (pricing and item balancing) | Medium (churn, renewal flows) | High (A/B testing, placements) |

Compliance requirements | High (GDPR, opt-in, traffic purpose clarity) | Financial + privacy compliance | Platform billing and opt-ins | Moderate (GDPR, IDFA use) |

User experience impact | Low (runs in background) | Low to moderate (Impacts limited to gating features) | High (subscription prompts) | Moderate to High (banners, pop-ups) |

| Potential audience monetization | Up to 100% of consenting users monetized | ~2–5% of users | ~70% retention after 1st month | ~95–99% of users exposed (region-dependent) |

Devices | Mobile, Desktop, Smart TV, Browser Ext. | Mobile, possible on Desktop, TV | Mobile, possible on Desktop, TV | Mobile, Web |

Possible Risks and Considerations of Internet Sharing SDKs

No monetization model is immune to scrutiny – and Internet sharing SDKs are no exception. While the model offers a compelling alternative to ads and IAPs, it hinges on the assumption that users understand and accept what’s happening in the background. That assumption doesn’t always hold.

There are critical factors worth evaluating before jumping in. Some are technical, some reputational, and some simply structural. Here’s what any team considering integration should consider.

- User consent? Bandwidth sharing must be clearly disclosed, and users must explicitly agree before any traffic is routed. Consent can be collected at install, onboarding, or later, but nothing should activate until it’s given. Apple, Google, GDPR, and CCPA all emphasize transparency and informed choice, though implementation standards vary slightly. If the opt-in is buried, vague, or misleading, both compliance and user trust are at risk.

- Isn’t this basically a botnet? At a glance, routing third-party traffic through thousands of end-user devices looks suspiciously like a botnet. The difference? Consent and transparency. Botnets operate without user knowledge or control, while internet sharing SDKs require clear opt-in, restrict traffic to non-invasive use cases, and comply with platform and legal standards. But the optics still matter, and even legitimate networks can raise alarms if poorly explained.

- Does it collect personal data? These SDKs aren’t designed to harvest contact lists, GPS, or identifiers. The primary asset shared is bandwidth and an IP address, and traffic is typically anonymized. Still, devs should verify that no unnecessary permissions are being requested, any data claims should match actual behavior.

- What’s the risk of slowing down the device? Most SDKs are designed to be lightweight, routing traffic only during idle periods and throttling usage to minimize disruption. But “lightweight” doesn’t mean invisible. Under real-world conditions, like low bandwidth, roaming, or battery-saving modes, even minor background activity can affect responsiveness or battery life. Though testing across edge cases is essential.

- Lack of transparency around buyers. SDK providers often list “brand protection,” “SEO monitoring,” or “market insights” as traffic destinations. These are categories, not clients. Developers rarely know who is actually routing traffic through their users’ devices, which leaves room for misuse or reputational blowback. What would establish transparency is asking for clarity on buyer vetting processes, resale restrictions, and whether third-party auditing is in place. If these answers aren’t forthcoming, it’s worth reconsidering the integration.

- Reputational fallout. Even if everything works as promised, perception matters. Users are sensitive to anything involving “background data” or “sharing internet.” If this isn’t communicated clearly (or if your app appears in headlines for the wrong reasons), expect uninstalls – and questions from partners. Developers might want to consider build opt-in flows that clearly state the value exchange, avoid burying terms in obscure clauses, and consider adding an always-available opt-out.

- Lack of auditing into SDK apps. According to security reviews by organizations like Guardsquare and Synopsys, many app developers do not perform deep audits of third-party SDKs, even those that handle network traffic or permissions. One should take into consideration the risk of data exposure or misuse.

So, who’s actually behind these SDKs, and what do they offer? Let’s take a look at the major players shaping the space right now.

Key Providers

Honeygain SDK

Honeygain is one of the most recognizable players in the internet sharing field. Launched in 2019, it began as a standalone passive income app, paying users small rewards for sharing idle bandwidth. It later rolled out an SDK, allowing developers to embed the same monetization layer into their own apps.

Honeygain emphasizes transparent consent and says the SDK has minimal impact on performance. According to the company, traffic is only sold to business clients for use cases like “price comparison, brand protection, web monitoring”. It complies with GDPR and CCPA regulations and maintains transparency through clearly documented consent flows and integration metrics such as opt-in rates, bandwidth contributed, session duration, and estimated earnings per user

Honeygain offers a self-service SDK with accessible documentation and integration code available after registration. It provides more transparency than closed or invitation-only platforms by allowing developers to review and evaluate the integration before entering a formal partnership. Payouts are based on geography – with monthly estimates ranging from $100 to $400 per 1,000 daily active users (DAU) in top regions.

Notably, in 2022 the company signed an exclusive partnership with Oxylabs, a major company in the proxy server industry, providing user-sourced IPs to power one of the largest residential proxy pools globally.

Platforms supported: Android, Windows, macOS, Apple iOS, FireOS, LG WebOS, Flutter, Samsung Tizen, Unity,

Bright SDK (Bright Data)

Bright SDK comes from Bright Data (formerly Luminati), the same company that once drew criticism for reselling Hola VPN user bandwidth. Today, it positions itself as a compliance-first infrastructure provider, emphasizing KYC checks, transparent opt-in flows, and a focus on public web data access.

Unlike traffic-based models often used by bandwidth marketplaces – platforms where developers get paid based on the amount of user data transferred (usually per GB) – Bright SDK pays a flat daily rate per opted-in user.Bright SDK pays a flat monthly rate per opted-in user. Monthly payouts range from $100 to $350 per 1,000 IPs, depending on device and region

The SDK code isn’t publicly available: integration requires a partnership or enterprise agreement. It requires a formal integration process, which may limit the level of self-service analytics or visibility compared to open platforms like Honeygain. Reporting and metrics may instead be handled through direct partner communication.

In exchange, developers gain access to an established infrastructure with consistent demand from enterprise clients in various fields. That could translate into more stable and predictable earnings compared to smaller or less mature networks.

Bright SDK has partnered with some established companies such as Wizard Games, Daemon Tools, and Aeria Canada. While its legacy still raises eyebrows in some circles, it remains one of the most established players in the SDK monetization space.

Platforms supported: Android, Windows, macOS, Apple iOS, LG WebOS, Samsung Tizen, Huawei.

Infatica SDK

Infatica keeps a lower profile and focuses on enterprise partnerships rather than broad developer adoption. Infatica’s SDK isn’t openly distributed, developers must apply for access via direct contact rather than downloading it. The company pitches “peer-to-business” bandwidth resale but publishes little detail about developer dashboards or integration workflow.

In 2021, the company drew serious transparency and privacy critiques, when reports emerged of it flirting with browser extension developers to include the SDK with limited disclosure. The company claims to vet clients and uses threat detection partners like Bitdefender to scan and filter outbound traffic. Estimated payouts are usage-based and vary by volume and region.

Infatica targets apps with high daily active user (DAU) thresholds and persistent background activity – VPNs, desktop utilities, and smart TV platforms – where network sharing can run continuously and monetization benefits scale with retention.

Platforms supported: Android, macOS, Windows.

Conclusion

Internet sharing SDKs aren’t magic, but they’re not malware in disguise either. One can think of it like adding a basement rental to your app’s monetization house: it’s out of sight, earns on the side, and only works if you lay proper plumbing.

For developers, the pitch is simple: most users won’t pay, but their devices can still contribute. This model opens a new revenue stream that doesn’t compete with ads or IAPs – it complements them. And yes, the numbers can be meaningful if you have scale and the right geography.

These SDKs handle live network traffic and affect how your app behaves in the background – which means Apple, Google, and your users will care how they’re implemented. The best providers build in safeguards: encrypted traffic, public data only, verified clients. Still, it’s on developers to audit what they ship, explain what it does, and respect what users agree to.

Used responsibly, internet sharing can play a solid role in a hybrid monetization stack. Whether it belongs in your stack depends on how it fits your product, and how well you can explain it to your users.

Proxy geek and developer.