OxyCon Day 1 Recap

We run through the web scraping event’s first day.

- Published:

You can find our recap of Day 2 here.

Organizational Matters

A few words about how the event is organized. Contrary to Zyte’s summit (which we recommend attending if possible), everything takes place online. Participation is free as long as you fill a lead capture form with basic information. Once that’s out of the way, Oxylabs sends you a link with login information, and you can access its streaming platform.

This year, the talks fall under one of three categories: infrastructure, development, and business. They all run on the same track, so the topics may switch from maintaining web scrapers in one talk to the legal implications of web scraping in another. You can write questions at any time, people can upvote them, and each talk has around 10 minutes for answers. There’s also a Slack channel for networking, though admittedly it’s not really bustling with life.

Overall, from the organizational point of view, Day 1 went smoothly. Some people had issues with getting their passwords emailed, but that was promptly fixed.

The Talks

Now let’s talk about… the talks. There were five in total, with the sixth one being a discussion on the legality of web scraping. The schedule was pretty tight, so we shared which presentations to watch and pooled our notes.

Talk 1: Managing Dozens of Python Scrapers’ Dependencies: The Monorepo Way

A very technical talk by Tadas Malinauskas, a Python developer at Oxylabs, that was aimed at other developers. I’m not sure why the organizers decided to start with it, but it is what it is.

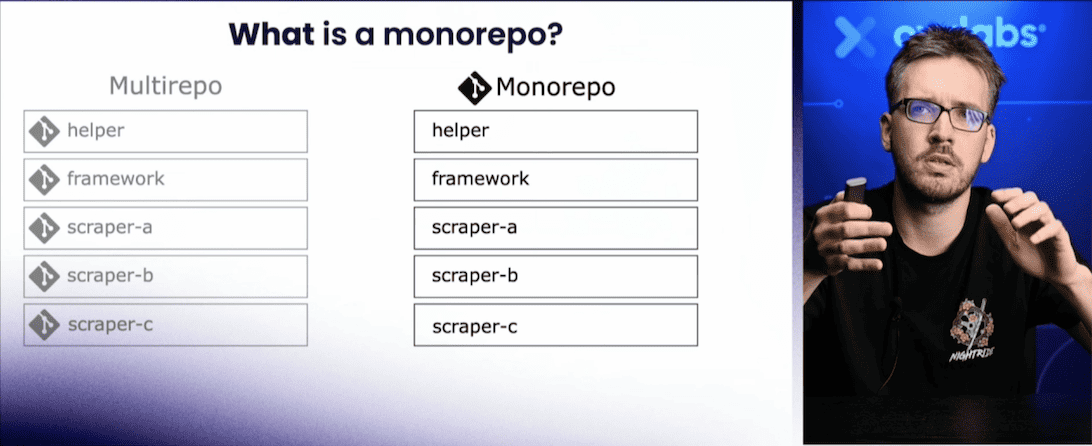

Basically, Oxylabs used to manage its projects using many repositories. This turned out to be inefficient, as each change (e. g. a bug fix) required creating separate merge requests for all dependencies. As a result, Oxylabs had a growing pain in optimizing the process.

To solve this, Oxylabs switched to a kind-of-monorepo approach, where multiple projects grouped by type fell under one repository. For example, one repository for web scrapers, another for data parsing, and so on. This resulted in fewer merge requests and faster development time (as it became easier to test projects locally when they were in one place).

The presenter then proceeded to demonstrate how to implement the monorepo approach.

Talk 2: How to Continuously Yield High-Quality Data While Growing from 100 to 100M Daily Requests

This one was fascinating. The speaker, Glen de Cauwsemaecker from OTA Insight, scrapes hospitality data from many sources and then presents insights to revenue managers. His presentation showed the growing pains and decisions the company has made to scale its data collection, going all the way back to 2013.

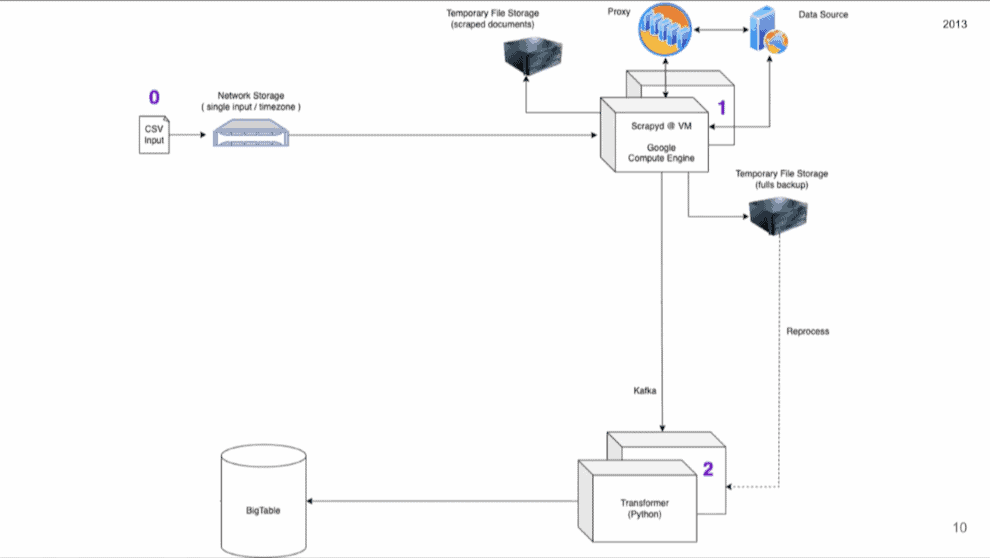

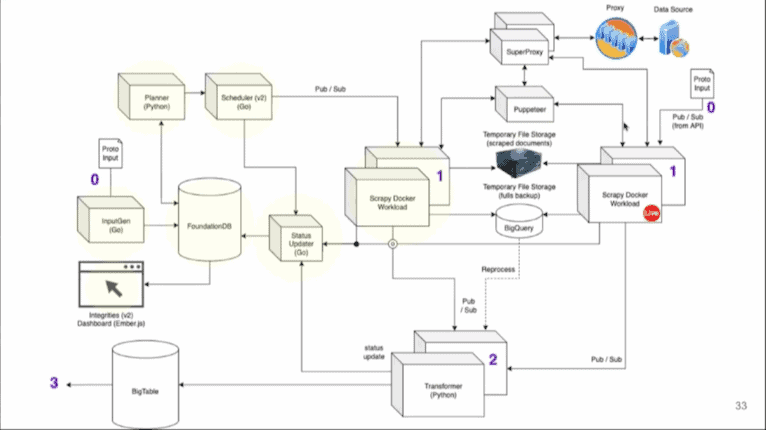

You can follow Glen’s and his team’s step-by-step process of building a web scraping infrastructure. For example, how they had to separate the crawler from the parser, as wrong assumptions meant redoing the whole scrape. How they introduced integrities to monitor and retry failed requests from giant crawler inputs. How they started scheduling tasks, built a super proxy to monitor errors, switched to Protobuf from JSON, outgrew two headless browser libraries, and more.

Each step was accompanied by a diagram to show how it impacted the infrastructure. By the end of the talk, you can understand how the left image evolved into what’s on the right (we’ll try to get better quality images):

The talk had some interesting questions, as well: why Protobuf? How to manage blacklisted proxies? What’s wrong with Puppeteer? How frequent is SSL fingerprinting nowadays? How to avoid CAPTCHAs? We strongly recommend watching this one.

Talk 3: Scraping for Government Use Cases: How to Detect Illegal Content Online?

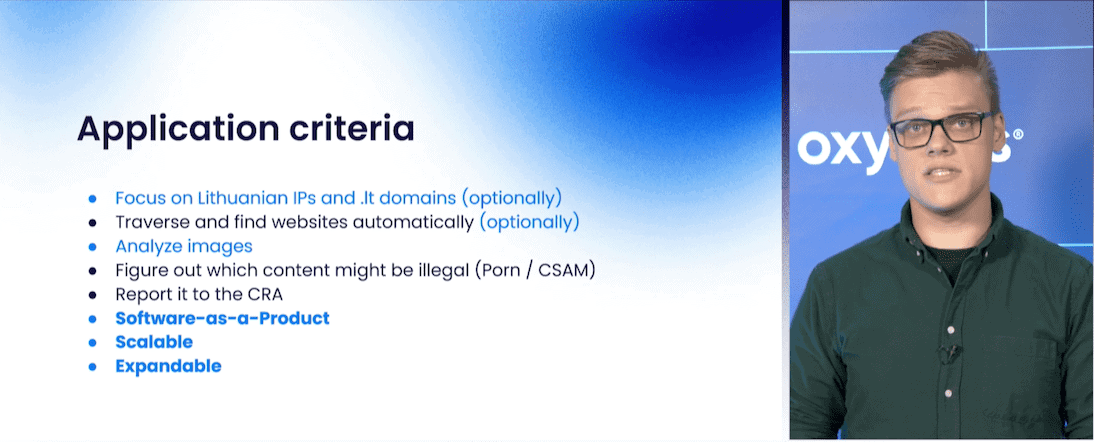

One more by Oxylabs. The company’s systems engineer, Ovidijus Balkauskas, spoke about the tool they built to detect child abuse and porn. It automated the process with web scraping, police-supplied hashes and ML-based analysis. The talk was less technical and had more of a “this is interesting” kind of vibe.

The talk’s two main highlights were: 1) working with public entities and 2) determining what exactly is Lithuania’s web space.

The first showed the constraints public entities have to deal with. This ranges from obligation to save taxpayer money (less room for experimentation, pressure to take the cheapest offer) to lack of qualified specialists and possible red tape. With this in mind, Oxylabs decided to build a tool rather than a service.

Determining the Lithuanian web space also proved tricky. Oxylabs couldn’t rely on .lt domains or Lithuanian IPs alone, so they took a combined approach.

Talk 4: How to Scrape the Web of Tomorrow

A talk by Ondra Urban, COO of Apify. Clickbaity title and a lot of self-promotion. But otherwise, it was a vibrant and fun watch, especially for people who’re only getting into web scraping.

The first half revolved around something Ondra called the art of opening a website. It gradually went through various protection mechanisms and how much web scrapers actually need just to open a website. A basic cURL request -> error, cURL + a user agent -> a different error – and so on. Very entertaining.

The second half switched to promoting Crawlee, Apify’s new web scraping and automation library. We kind of tuned out at this point; but if you prefer to scrape using node.JS, Ondra did a good job going through Crawlee’s main functionality.

Talk 5: How hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn and Cases Following It Have Changed U.S. Law on Web Scraping

A lawyer’s take on the legality of web scraping. The speaker, Alex Reese, focused on the hiQ v. LinkedIn case through the lens of CFAA (America’s anti-hacking law). Alex’s firm represented hiQ, so it’s impressive to hear about these matters from someone who experienced them first-hand.

Alex started with an overview of the CFAA and how it grew to apply to web scraping (which obviously isn’t hacking). In short, platforms argue that data behind a login is on a protected computer, and scrapers are not authorized to access it. Even if they are, sending a Cease-and-Desist revokes authorization. Platforms also made an argument that this affects public data that was later made private.

Alex then went through a real Cease-and-Desist letter sent by Meta, explaining the arguments of both sides.

Afterward, he listed arguments made in the hiQ v. LinkedIn case and what the decision means for web scraping. In short (don’t quote us, we’re no lawyers): scraping public data is legal; the case created grounds for narrowing CFAA; courts started questioning whether the behavior of platforms was anticompetitive.

Finally, Alex presented some more recent cases relevant to web scraping (such as Van Buuren v. the US or Sandvig v. Baar).

Panel: Lawyers Discuss Scraping

The panel had five lawyers: Denas Grybauskas from Oxylabs, Sanaea Daruwalla from Zyte, Alex Reese from Farella Braun and Martel, Julius Zaleskis from Dataistic, and Christian Dawson from i2Coalition.

It was an interesting discussion covering several relevant topics for web scrapers: issues surrounding data collection, best practices, how to scrape personal data in the US and Europe, how to distinguish what is sensitive data, how to protect yourself against lawsuits, and more. It’s a must-see if you’re doing any kind of data collection.

Aside from useful advice, the general gist was that web scraping is still a legal gray area, and much is unresolved.

The panel discussion also included an announcement: Coresignal, Smartproxy, Oxylabs, Rayobyte and Zyte are jointly starting an Ethical Web Data Collection Initiative. Its goal is to improve the image of web scraping and jointly communicate with legislators about matters concerning the industry.